This is the second post about Denys Gorbach’s new book on Ukraine: The Making and Unmaking of the Ukrainian Working Class. The first post is here.

In the period between writing the first post and this one, Michael Burawoy has died. Burawoy was one of the formative influences on both Gorbach and me. Here’s a short excursus on how he influenced our approaches to writing a novel (in the Ukraine and Russia contexts) form of political-economy-ethnography. I hadn’t intended to focus on Burawoy (because there’s so much else of interest in the book), but here goes.

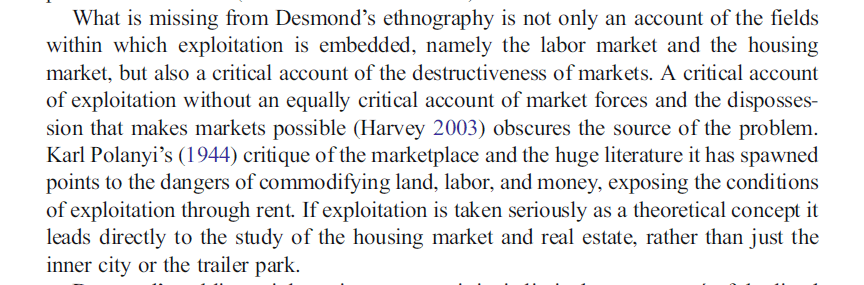

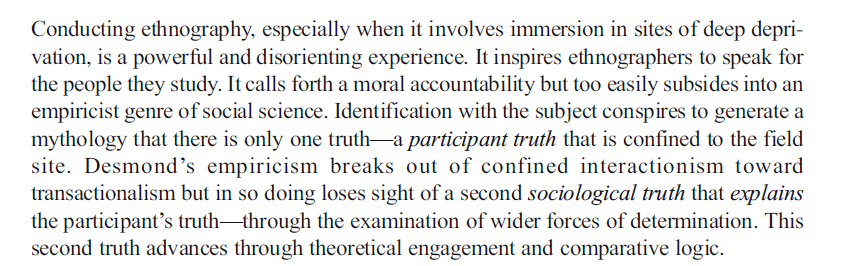

Both Gorbach and I try to synthesise our cases from what Gorbach calls ‘participant truth’ and ‘sociological truth’ – and here he cites Burawoy’s 2017 piece. Burawoy there argues that ethnography needs to be liberated from the naïve empiricism that still plagues anthropology and sociology and which is continuously re-invented by scholars unwilling (or afraid) to confront the political implications of their own work. Burawoy uses this opportunity to make the case again for bringing structure and comparison to any micro-level work. Only by linking specific ethnography cases to the broader structural constraints (oligarchic capitalism in Ukraine/authoritarian neoliberalism in Russia) can research do justice to the ‘common sense’ of interlocutors. This is what Gorbach and I attempt. The social ‘facts’ of cases do not speak for themselves. And this, via Bourdieu, is a point Burawoy hammers home in his robust writing. At the risk of overshadowing the discussion, it’s worth citing Burawoy further (here reviewing contemporary ethnography of Wisconsin):

While there’s much more to say about Burawoy’s influence, I want to turn to Gorbach’s very extensive discussion of politics in his second chapter (and the empirics of Chapter Nine). As I wrote previously, Gorbach makes a pitch for those interested in Ukraine to take more seriously ‘everyday politics’ and ‘moral economies’. Having said that, he starts off with a welcome ‘intervention’ – one highly topical to the ascent of Trump 2.0: to paraphrase – to take populism seriously we need to move beyond discourse analysis (MAGA, get rid of woke, etc), and use empirical tools like ethnography to uncover the material basis for populists’… popularity. I’ve mentioned in this blog many times Arlie Russell Hochschild who wrote two books on the Tea Party and Trumpism, but it’s indicative of the timidity of indigenous US political sociology/anthro that this barely scratches the surface and does not qualify as ethnography in way that Gorbach’s or my work does. Gorbach has lived and worked with his interlocutors, as have I. One can barely imagine this possibility in the class-fractious society of the USA. Yes there are some exceptions, but they still amount to general handwringing, or poverty porn. The truth is, an intersectional yet working-class ethnography is just not going to be interesting to the scions of Anthro in the US who get to do PhDs by virtue of precisely that privilege that would make it unthinkable for them to do the necessary work. (For a good general anthro account of Trumpism, see Gusterson who rightly says it ain’t all about class, yet…. ‘Trump’s victory confronts US anthropology with an incompleteness in the project of repatriated anthropology. While anthropologists of the United States have been busy studying scientists and financial traders at one end of the social scale and crack dealers and immigrant communities at the other, we have not had so much to say about the middle ground, the people who supported Trump—people we tend not to like.’ Shout out here to someone who HAS done this work, only in the UK context: Hilary Pilkington. Shout out to, to Christine Walley

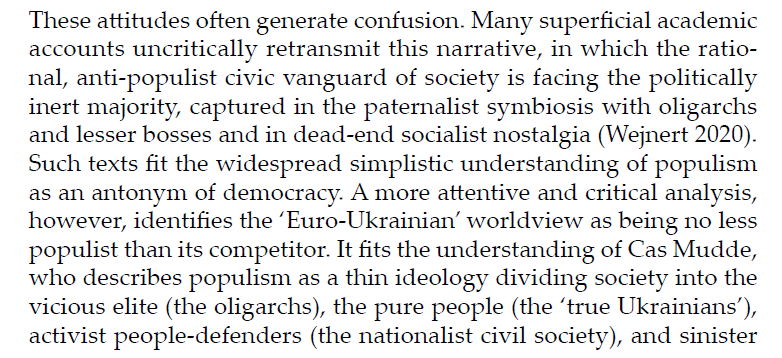

Gorbach reminds readers that the best work on postsocialist populism emphasizes its shadow relationship to democracy, avoiding the normative stance that opposes democracy and populism and which is so frequently deployed to show how ‘defective’ Eastern Europe is by mainstream observers. Gorbach, following the work of Tarragoni and Canovan, argues that populism, while expressing a crisis of representative liberal democracy, is not a ‘thin ideology, but contains a radical democratic critique of representative government. But what’s missing is what Gorbach and others aim to provide – the material basis of populism’s rise which ‘aspires to distribute income and, nourishing illusions about the function of the state, is politically disorganized (Boito 2019: 135.)’. In an abrupt turnaround though, Gorbach’s innovation is to relegate populism as just a Gramscian ‘morbid symptom’ of the crisis of capitalism. Parapolitical processes that themselves are generative of populist ‘supply’ are more important to look at and these are perfectly adequately grasped using the long-standing terms ‘moral economy’ and ‘everyday politics’. The ‘crisis of representation’ that populism reflects is then doubled in scholarship: mainstream liberal political science has no tools with which to move towards a diagnosis of the disease (it ignores those that Gorbach offers here), instead offering ‘game theory’ or the pseudoscience that is ‘mass’ social psychology and which includes bizarre claims about whole ‘national groups’ on the basis of dubious experiments conducted on American undergraduates which cannot be replicated and remain ‘WEIRD’.

Gorbach returns to his problematizing of ‘populism’ in the empirical chapter on language politics in Ukraine. There’s an enlightening discussion of how pro-Ukrainian language narratives align with upwardly mobile citizens after Maidan, how the far right may find allies in LGBT organizations in opposing ‘vatniks’. A ‘thin patriotic identity’ (before 2022) emerges that papers over deep ideological differences among liberals and nationalists (p. 224). Uniquely in Ukraine, language affiliation plus civic involvement then serves as a way of denying (or exiting) a stigmatized working-class identity. But, as Gorbach continues:

At the end of the same chapter, Gorbach shows how ‘East Slavic’ Nationalism acts no less powerfully (and does not necessarily conflict with) the ‘ethnic’ Ukrainian model. Indeed, in a place like Kryvyi Rih (recall, Zelensky is from this city), Gorbach uncovers an inversion of the ‘vatnik’ theme – ‘stupid nationalists’ and ‘civilized Soviet-type people’.

After a long discussion of the mayorship of O. Vilkul who would later become a key figure that confounds stereotypes about the political views of Eastern Ukrainians, Gorbach concludes this section:

However, ‘One must take seriously the words of many adherents of both camps when they say they are not ethnic Ukrainian or Russian nationalists. The root of the political cleavage is the perceived moral difference between the self and the other rather than ethnic animosity.’ And in a subsequent final post about this book we will return to that topic of moral economy how it expresses everyday politics.

Pingback: Unmaking the Ukrainian working class Part III | Postsocialism