With co-author Charlie Nail

While it was an unalloyed good to see so many people released from wrongful custody in Russia, the congratulatory and celebratory rhetoric surrounding the events was a distraction; the vast majority of prisoners without any media profile remain in custody and some may die in prison, as the musician Pavel Kushnir did on 27 July. The response: ‘getting anyone out is a victory’ obscures the fact that especially among the Russian nationals released this happened because they had vocal or powerful supporters, or because it was in the interest of the Russian state.

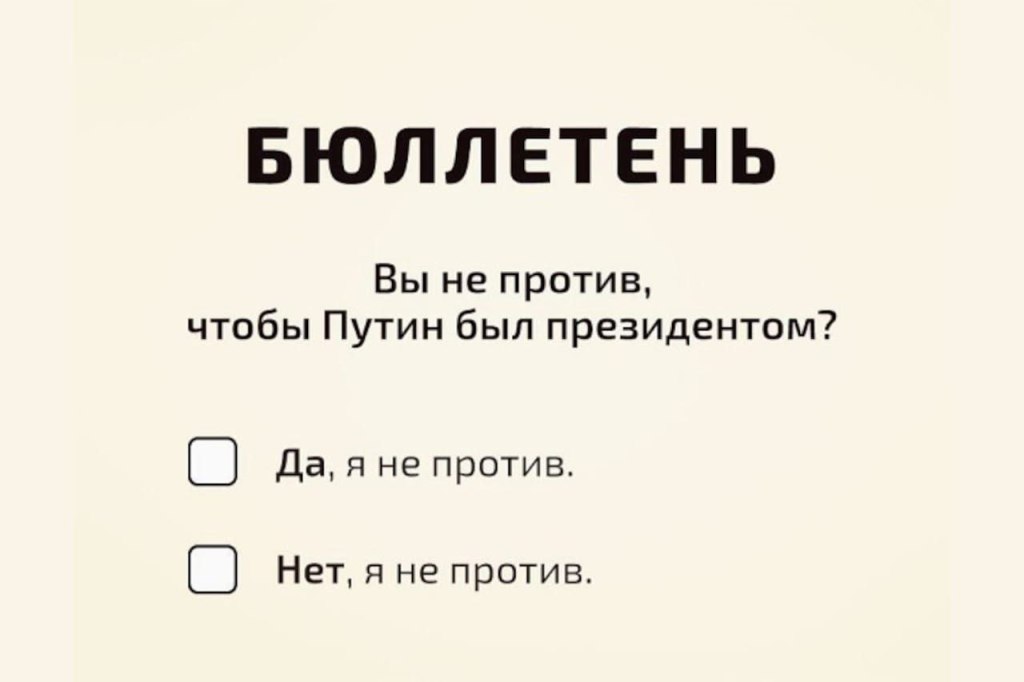

The hard truth is that thousands of victims remain in prison, if we include Belarus in the equation. Secondly, the moral victor/victory tone – as well put by vlogger Vlad Vexler – obscures the hollow political meaning of events. Partly it could be explained by an emotional shock of the speakers who just a few hours previously were in prison. But it shows the fruitless search for a viable political language through which people – whether in exile or still in Russia – can engage with compatriots and provide counterarguments to the broad consensus around ‘encirclement’ and ‘my country, right or wrong’ that’s increasingly apparent in Russia.

To be fair, this was actually the main opening message of the group. Yashin spoke very movingly of how much he wishes he could go home – surely because he knows that his political career ends in exile. The point of saying ‘Putin does not equate to Russia’ – made by more than one speaker – was not, as widely interpreted, about denying collective responsibility or deflection, but correctly identified the main political problem – how to drive a wedge, how to begin to create an alternative imagined future for Russia among Russians.

However, an unfortunate side-effect of that correct deduction was the focus, right at the beginning of the presser, on dubious things like educational visas for Russian youth as a form of educational soft diplomacy. The presser provoked predictable howls of outrage from the usual suspects, unhappy that some speakers had gone even further and made a point of arguing against sanctions – on the grounds that Russians and the regime were not the same thing. This was indeed ill-advised, particularly by Kara-Murza. Surely this can’t have been the priority? In 2022 this argument might have had legs but not in 2024. Now, I’m on record as arguing that blanket visa bans and the like are counterproductive. I’d still argue that allowing ALL Russians to easily leave Russia (and the EU is the closest set of countries to find work or to experience the reality that the west is not a Russophobia machine) would be a pretty effective anti-regime policy.

However, in reality, those who yesterday spoke against travel bans and sanctions were consciously or not arguing for the restoration of their rights *as a class* of extremely privileged Russians – and not on behalf of the majority of Russians who have never had an opportunity to travel or study abroad (69% according to Levada-Center 2022 poll) This is why, although they might sincerely think they are speaking in defence of their national collective, in reality they are arguing for class interest and inadvertently revealing how the main discourse among the small but vocal group of Russian ‘opposition think-leaders’ in Europe and the US is really about an ‘antipolitical’ technocratic approach. In addition, this quite narrow interpretation of Russian rights (travel to the West) gives more fuel for regime propagandists to deflect growing dissatisfaction of ordinary Russians by the war: ‘look, these westernized traitors are self-serving’…

It’s hard to say how strong the influence of Mariia Pevchikh is. She’s Navalny’s FBK successor in all but name and she was at the heart of the photo-ops, claiming to have helped put together the list. We detect even in these hurriedly put together speeches further competition for brokerage vis-à-vis Western elites under FBK’s (Pevchikh’s) tutelage. The ‘drop sanctions’ = restore visa/bank account facilitation is a dead giveaway. Nothing could be further from 1. How to help Ukraine ensure its sovereignty and security (even short of ‘victory’) and 2. How to address as political subjects the vast majority of Russians who have never even travelled outside their own geographical region within Russia. Whether the released prisoners are conscious of it or not, the talk reveals more deployment of rhetoric (here it was understandably moral and emotional) to perform deservingness and be ordained as one of the ‘good Russians’. To serve as a filter for other good Russians – in the cause of retaining ‘civilized’ rights as global citizens.

Back to the circumstances of those released. Mariia Pevchikh in claiming ownership of the list was, to reiterate, staking claim to brokerage – and to political influence over Western decision-making on behalf of the organization FBK, now a completely transformed political animal. This was as distant as one could get from the ideals of Yashin – who said he’d been traded against his will and only wished he could go back to Russia, where, unlike many savvy exile brokers, he has been already elected once as municipal deputy. While Pevchikh’s first words sounded unguardedly celebratory – as if she welcomed the continuation of exchanges in order to benefit from the PR, she more carefully checked herself, saying ‘not at the expense of Putin catching more foreign journalists’.

Kara-Murza got a lot of flak for his comments in opposition to sanctions ‘against ordinary Russians’. Who is Vladimir Vladimirovich K-M? A third-generation very well-placed journalist who came to prominence in opposition politics thanks to the sponsorship of oligarch Khodorkovsky. He strikes us as a sincere person, survived several assassination attempts, but the fact is that 99% of Russian people have never heard of him (and if they know his name it’s more likely they are thinking of his father). Indeed, he is what Russians call a classic ‘mazhor’ (a ‘major’ – which could be translated as ‘gilded youth’, ‘silver-spoon’, or ‘nepo-baby’: people whose family provided them with every study and career opportunities closely connected with the privileges of the ruling elite but unavailable for ordinary people). In the Russian world of undeserving clientelism it has a decidedly bitter and unpleasant connotation since the Soviet times.

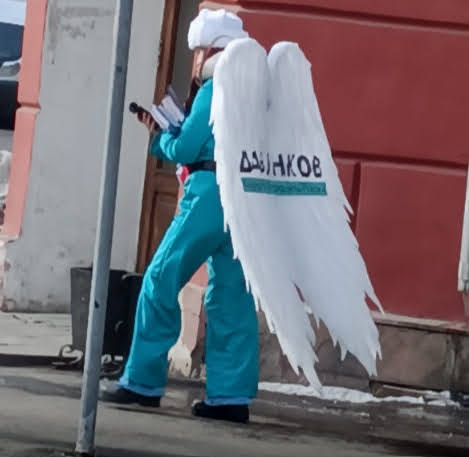

Alongside Ilya Yashin, K-M even looks rather incongruous. Once again, one need not doubt his motives or sincerity to see the contrast. Yashin, in our view was expelled for good reason by the regime. He remained one of the few well-known charismatic leaders of anti-war protest. He might even have been more dangerous in the long run than Navalny. He is not a rich kid (unlike Kara-Murza), he has a biography that is understandable to Russians (his mum and dad are engineers, he earned money through ability alone and served as a municipal deputy). He is a master of protest actions. Now he’s abroad, he is no longer ‘with the Russians’. Both the government and Yashin understand this perfectly well. Yashin said wisely yesterday that he will watch and listen to the emigres, but the main politics should be in Russia (It is amazing how fresh his head is for someone who has served time). Yashin has been consistent on the need for consolidation among opposition, for olive-branches, and for building street protest to show ordinary Russians how not to be afraid. David White wrote about these strategies and tactics in 2015.

We are not the only people to note how the discourse about ‘deserving’ and undeserving among the émigré oppositionists reflects ideas about hierarchy and privilege no less ingrained than among the regime players themselves. The moral purity arguments about ‘good Russians’ so visible among these emigres, and all the talk of lustration carried out by brokers has probably been internalized thanks to easy translation of cultural capital by people like K-M – graduate of Trinity Hall, Cambridge University (where of course he researched dissident movements in the USSR) into political capital in his reception by the US State Department – ‘I can explain who the goodies and baddies are and how to change Russia’.

But Yashin worked like everyone else (and was not ‘placed’ there from birth, like others), sat like everyone else (but not K-M) in a common prison cell. As soon as he was taken out (allegedly at the instigation of Pevchikh), he becomes different from everyone else. This is the goal of the authorities – to show people that he is one of those ‘globalists’ and not really Russian. That’s why they kicked him out without a passport, but formally retained his citizenship – it might be to give him a reason to promote the idea of a “good Russian passport”, which the Russian Antiwar Committee had already been discussing and which post-Navalny’s FBK had rightly called ‘all that crap’.

What’s the upshot? The deep class division that existed in pre-war Russia has only worsened and everyone became completely atomized. The rich, who had enough money to emigrate or left early, and who now are asked where their money came from, are behind the idea of special passports, special accounts and lustrations (Schulmann, Pevchikh, Volkov, Kara-Murza, Katz, Margolis, Gudkov). They are the loudest. The poor emigrants survive in ‘second-rate’ Tbilisi or refugee status. They are ‘the mass’ used by our wonderful brokers to show their popularity and representativeness of the emigrants. Russians within the country are not taken into account.

Having realized that she won’t get any dispensation from Ukrainians, Pevchikh seeks to use 1. Kara-Murza to exemplify her ability to select good Russians from the clutches of the regime, State Department approved; 2. Yashin represents the selection of good Russians minted by anti-war movement of Russians themselves inside Russia (whether he was on the original list or not is irrelevant); 3. Skochilenko represents a kind of legible westernised sexual minority and art communities) and, 4; we mustn’t forget the coordinators of Navalny’s headquarters who did not earn enough money to emigrate early enough (‘we don’t abandon our own’). That’s why there are even more urgent cases who didn’t make the cut about whom Yashin spoke yesterday (Gorinov and others, and also people like Pavel Kushnir) – they are no-names, there are no ‘target groups’ for their release. But their release would be more dangerous for the regime: it would be a signal to the intimidated Russians: ‘look, the rich kids and Europe are taking care of ordinary Russians.’ Russians might start wondering if Europe is really that bad, and the regime really wouldn’t like that. It’s convenient for them when there’s their image as a ‘bloody regime’ on one side and a rotten West on the other.

Pevchikh and others played right into Putin’s hands. They worked precisely on the target audiences needed by the regime in order to emphasize how alien the liberated Russians are. And at the same time, she worked according to the Western agenda, providing a serving of ‘legible’ victims according to the West’s target audiences. If Yashin gets the hang of this new vista and shapes his own agenda: great. If he starts promoting an anti-sanctions agenda for those who have already left then it means he has fooled himself. As for K-M, his fantasy-dream CV (elite job in Russia since age 16, Cambridge education, US residence permit, reception in US govt bodies, and political sanctification by the age of 30) is why he was kept in solitary in prison – the authorities were worried he’d be killed by other prisoners. What a perfect way to continue discrediting the opposition by releasing him back out to the wild.