Another post this week reviewing some goings-on in the Russia-sphere.

Biopolitical entrepreneur Katya Mizulina and head of the ‘Safe Internet League’, who is the daughter of politician Elena Mizulina – herself a pioneer in socially conservative legislation – was asked at an event by a brave journalist why she rails against Western ‘child-free’ ideology while not having any children of her own. ‘Child-free ideology’ (sic) is just the latest addition to the not-very convincing attempt to consolidate Russian identity around the message that ‘we’re the protectors of the real Judeo-Christian tradition unlike the decadent Ukraine-nazi-supporting West’.

My new book (announcement forthcoming) opens with a look at the imposition of a new kind of civics lessons on school children. The very first ethnographic scene features a middle-aged male Life Skills and Personal Safety teacher who implores a room of teenagers to read the bible and recant of their pro-Western attitudes. Let’s just say these unwelcome distractions from the curriculum by unqualified and under-prepared instructors don’t go down very well with children and parents alike. Unlike the new social conservatism, there is an audience for patriotic education classes, where they are accompanied by genuine social and economic resources like preferential places at university. Young people are just as entrepreneurial as politicians in using political agendas in education to get ahead.

I’m not much of a fan of podcasts, but the Meduza Russian-language ones are often hidden gems. Like this talk with Maksim Samorukov about the informational isolation and blinkered world-views which ‘informed’ Saddam Hussein’s decisions to invade Iran and Kuwait. In making links to Putinism, Maksim stressed how subsequent endless uprisings were easily put down, even after military defeat… And that society’s dissatisfaction just isn’t part of regime calculus once elites get used to the idea of supposedly limited wars as a substitute for domestic programmes and legitimacy.

Maksim also emphasized the irrelevance of ‘new’ or contradicting information for these leader-types. Revelations that to you and me could challenge our priors (like the effect on US foreign policy of an election year – very topical) is merely incorporated into the existing world-view of the isolated person (Mr Putin, or Saddam). This podcast prompted me to finally start reading this book about the Iran-Iraq war. Some day I’ll do a post on the parallels between that war and the current Russo-Ukraine conflict. An interesting note about Saddam’s decision-making: some argue we have a really good idea of this because he recorded himself so much on audiotapes which were subsequently captured by the Americans.

There’s so much being written right now about the looming problems in 2025-26 for the Russian economy and I can’t fit it all into this short post. In 2019 I discussed neo-feudalization of Russia’s political economy (“people as the new oil”). Many others have takes on this, from the idea of a new caste-like society with state bureaucrats as an aristocracy, to a more nakedly transactional ‘necropolitics’ where blood is exchanged for money (death payments for volunteer troops). Nick Trickett’s piece in Ridl argues against the ‘hydraulic Keynesianism’: that military spending boosts economic growth. Demographic decline and war are like a Wile E. Coyote cliff-edge for growth, a precipice towards which the Russian war stimulus merely accelerates the economy. Monetary policy like a 20% bank rate, ‘cannot tame what’s driving inflation’.

One of my informants on a very good blue-collar supervisor wage played ‘jingle-mail’ recently and moved back in with his parents. He’s 39 with no children and working in a booming manufacturing sector. He’s also working double-shifts to keep up with demand, but there’s a human limit to over-working in place of capital investment. Nick’s piece points to the stagnation in productivity in Russia.

Another sign of the endless war to make citizens fiscally-legible to the state is this story about ratcheting up penalties for Russian drivers who obscure or hide their number plates. Traffic cameras are, to an absurd and unpopular degree, relied upon to raise tax revenue in Russia. I’ve written about this many times on this blog. The details this time are not so important, but the story illustrates a number of things – penalties are still pretty low for all kinds of avoidance and ‘resistance’; Russians are ingenious in making their fiscal radar-signature as small as possible; the technocratic approach (blocking an AliExpress webpage selling revolving number plates) of the government is wholly ineffective because the state is losing capacity due to the drain of the war.

Does this shorter and more frequent posting by me signal a trend (a move towards the style of Sam Greene’s excellent, short-form weekly posting)? We’ll have to see. Though the news from my Dean of Faculty that she proposes closing all language-based Area Studies degrees may indicate I will have more time on my hands in the future. At Aarhus University we’ve developed unique programmes where students attain a high competency in one language out of Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Hindi, Brazilian Portuguese, and then can go on to a Masters degree where they are team taught by experts beyond their region. So a Russian student gets exposed to expertise in Chinese politics, Brazilian environmental studies, and so on, regardless of their continuing focus on a single language. We also just began to expand Ukrainian studies and have two Ukrainian scholars working with us now. ‘Dimensioning’ [Danish Orwell-speak for cuts to staff and student numbers] of Area Studies will likely mean no language teaching in these areas in the future. We live in a time of narrowing horizons for students, unfortunately.

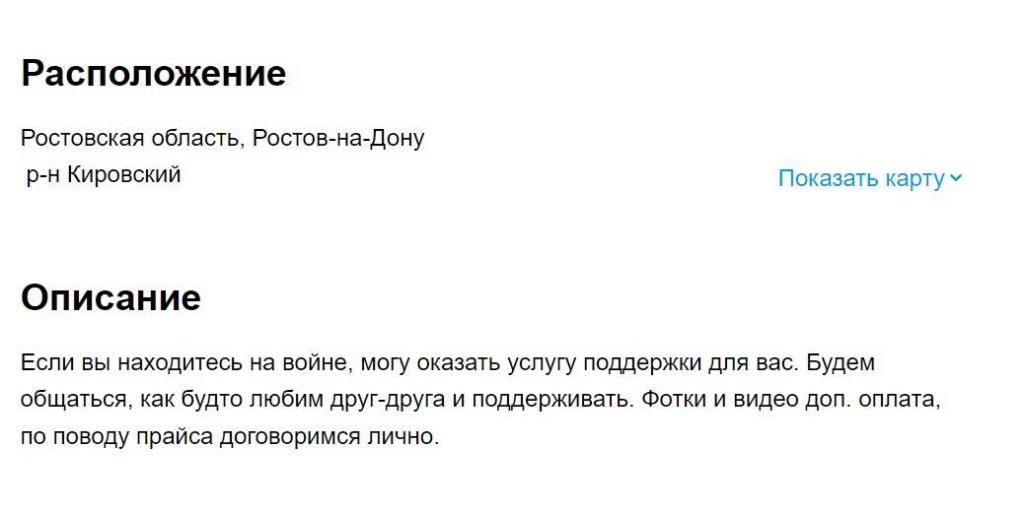

I leave you with this advertisement for war-time intimacy from Rostov: ‘If you’re at war I can provide a service to support you. We’ll communicate as if we love each other and support each other. Photos and video for an additional fee. Agreement about price subject to personal negotiation.’