Here I document failure. Is thirteen* rejects an unlucky number?

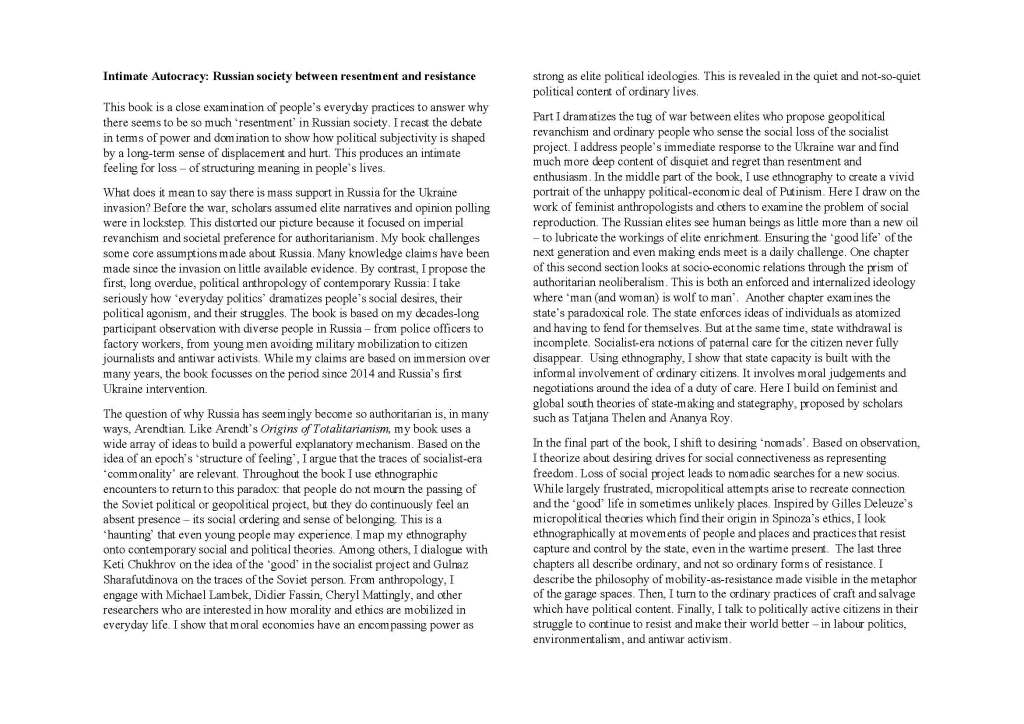

Some readers might know that in 2023 I wrote a book I had been planning for many years. The idea of the book is simple: Despite all the efforts to make the political ‘off limits’ in Russia, we can use ethnographic tools and anthropological senses to uncover political actions, dialogue and ‘subjectivity’ – in all kinds of unlikely places. And the war on Ukraine does not change that, even as it alters the political’s expression and visible forms. This book is an ambitious sequel to my 2016 ethnographic study Everyday Postsocialism. I won a competitive foundation grant that allowed me time to write the manuscript in 2023.

I thought, mistakenly, that I would be able to pitch this book successfully to an appropriate US university press. Perhaps to one which is interested in books about Russia. I have a good working relationship with many presses for whom I write ‘reader reviews’. These external reviews are the main way such presses make decisions about whether to give an author a contract. Typically, a press editor (full-time employee) looks at a short pitch, and if they like it they send it to two or more external reviewers who are academics at different universities. They sometimes pay these reviewers a few hundred dollars. After 6-12 weeks the reviewers write a report. If the reports are favourable, the editor *can* offer a contract.

Here’s a (simplified) timeline of what I experienced with US university publishers.

#1 – Senior Editor (for whom I’ve written reviews, often at short notice) of C****** U Press sits on my proposal for a few weeks, then sends it to a colleague (political science) who “has assumed sponsorship of projects in areas that your book covers”. After six months this editor still does not respond, so I leave a message on her voicemail. She then writes to say my messages got lost in spam. After another month she praises my topic and approach but writes: “I’m afraid that the project is not something that quite fits what I’m currently looking to acquire, and I’m afraid I must decline the opportunity to pursue it further”.

#2 Immediately, I sent the pitch to P******** U Press because my book engages a lot with a work recently published by them and which is considered a landmark in the field. I got no reply.

#3 Then I sent the pitch to S******* U Press where a good book on a similar topic had been published recently. Again, the anthropology editor passed me to political science who answered: “I had the chance to read the proposal. With regret, I must tell you that I’ll need to pass on taking the book forward here”.

#4 I then wrote to D*** Press. They publish a lot of ethnographic work with a critical political edge I admire. The editor replied: “Unfortunately, it isn’t something we can take on but I wish you the best of luck finding a home for the project.”

#5 After these two instant rejects, I wrote to T****** U Press which has coverage of both anthropology and Russia. An editor kindly gave me a lot of feedback with his rejection. He found it a “daunting” read, “dense with concepts” – I agree with him. “The book as a whole is just too much for me: too many substantial ideas, to many [sic] literatures to engage with, too many elements to keep in mind all the way through to the conclusion.” He advised me to send it to one of the presses that had already rejected. He also asked his colleague in anthropology to consider it, but she did not reply to my emails.

After this, I asked for some feedback from senior colleagues in the US (as well as others). They were very kind in helping me rewrite my pitch to be more accessible, simpler (I also rewrote the introduction to the book to ‘dumb it down’). I changed the title to be less interesting (obligatory). I also pitched the book to be more about society at war.

#6 Then, I sent it to U of C****** Press who published one of my favourite books combining theory and ethnographic flavour. They desk-rejected it: “I wish I had better news, but your project is not an ideal fit for our list, given the fields and approaches we are emphasizing at present”.

#7 Then, I wrote to editors at F****** U Press who have a relevant series I admire. After a delay (a trifling matter of four months) they wrote: “It sounds like important work, but I’m afraid that, with all the projects we already have in the works, we had better say no.”

#8 Then, I wrote to N** Press who had been recommended to me. After I reminded them of my existence a few times they sent the pitch to an historian of the 19thC for advice and then wrote: “I’m sorry to let you know we have decided to decline. The reader agreed that you have some great ideas, but she had trouble following the argument.”

During this process I canvassed colleagues on Facebook who gave me advice, most of which while well-meaning was little use. They said things like ‘go with the editor you think is good/responsive not the press’; ‘presses are not well adapted to interdisciplinary topics’; ‘It’s soooo difficult to overcome clichés and stereotypes among editors when you pitch something non-conventional’; Numerous US colleagues also said they had had great experiences with the same editors who had desk-rejected my book. They, usually embedded in a strong US-based network, expressed surprise at my experience.

I tried some other American uni presses (#9, #10, #11, #12, #13) whose editors never got back to me/ghosted me, as well as some non-US presses. This post only covers the North American experience and I present it without any further commentary. I know the shortcomings (and strengths) of my own MS and the pitch. But the post is long enough already. My short (1 page) and long pitch (with chapter synopses) can be read (and judged!) as PDFs in the research page of this blog. The MS is ever-evolving.

So what’s the problem? In my case it’s a few things at once. Not a dumb enough pitch (yes, people say this). Sensitive topic. Interdisciplinarity (probably the biggest problem). relative ‘high concept’ – yes, this is now a problem even for academic presses. The sales/acquisition model of US university presses (has to be sellable to public, though I think this is actually a myth). Lack of the right patrons ‘to put their fingers on the scale’ (to essentially blackmail editors, is what I’m told).

I’m reminded of this article by Ann Cunliffe on academia’s increasing narrowness because of the gatekeeping systems of journals and institutions. Despite the rhetoric, a cursory glance at some publisher lists really does reveal the McDonaldsization of social science academic publishing. She writes that we are exhorted to be ‘original’, ‘insightful’, ‘theoretically radical’, ‘fresh’, but the hidden message is to be the opposite. Articles, but especially books, should be about monocausal cases in tight time-frames, US-centric (even if about other places in the world), methodologically highly conservative, ‘politically radical’ in way emptied of radical politics, abstractedly empirical (we don’t want to scare readers by showing how data and big concepts change the meaning of each other), and finally: designed to meet criteria which promote our institutional advancement and not promote knowledge. It also seems that US academic publishing is a very good example of so-called Russian-style ‘patron-clientelism’, otherwise known as ‘blat‘. One US colleague said, ‘well, you don’t have an “in”, what do you expect?’.

As of writing, I do have a good relationship with a non-US publisher, so I hope this book will see the light of day sometime soon. And at least the Europeans didn’t write that a book about Russian people as political subjects was ‘too complex’ to understand.

*I consider my thirteen rejects to have beaten Vladimir Gel’man’s record of twelve attempts for his first book. (This is my third monograph…. and eleventh book overall).

*2025 update – the book came out relatively quickly with Bloomsbury Academic via their UK editor. And at a good price point for such a book https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/everyday-politics-in-russia-9781350509313/