People can tolerate autocracy, but they can’t tolerate the absence of hope in the future

The Russian presidential election presents us with a paradox that itself is something of a sea change for the meaning of politics today in that country. There was a pronounced shift. The election was likely no more unfair than before, but this time it’s almost as if the riggers had clear instructions – don’t even bother to try to make it look like you’re not rigging it. Just write in unbelievable numbers – unbelievable even for loyalists. At the same time, people I know who had long given up voting, and who more or less openly had admitted the disaster that had befallen their country since February 2022, almost with a sense of comfort went to the polls to cast a ballot for Putin. And thus, you have three likely truths of the electoral process – 20 to 30 million of the 64 million votes for Putin were just written in; the true turnout was pretty low because with electronic voting you don’t actually need physically coercion of voters; perhaps many more apolitical people than before voted for Putin. Why the last one?

Precisely because of fatigue, anxiety about the war and the knowledge that the decision was his alone but that the whole country is hostage to it. So, in my sample it was notable that while there is a hard core of Left Nationalists and Right Nationalist voters (let’s face it, the names of the parties are unimportant now), many switched for the first time since 2004 to Putin. For me, it’s just a bit unfortunate that few observers ever really go beyond the “falsification yet genuine popularity” framing of elections in Russia. This means that in 2024 they are not really prepared to unpack the genuine consolidating effect of the war on voting. Once again, I have to choose my words carefully, but let me offer an illustration:

My good friend Boris* is 40 years old. He’s a metal worker in Obninsk, a town an hour and half from Moscow. He has a degree in marketing but can’t find a ‘white collar job’ that’s worth the hassle. He took this job in an aluminium factory as a hedge against being drafted to the war. He has two dependents and a wife who works for the state. He likes reading American self-improvement literature: ‘how to think yourself into getting rich’, and he mainly talks to me about how to trade crypto currency and neuro-linguistic programming.

He, like many, had a kind of mini-breakdown in February 2022, saying things like ‘now the Americans will destroy us – what the fuck was the old-geezer thinking?’ But now he generally communicates in a highly ambivalent way – in memes that are not pro-war, but which always indicate the double-standards of the West. He approvingly notes the jailing of regional businessmen who have resisted the nationalization of factories important for the war effort. Like many interlocutors, he’s rather keen on any news stories, even obvious hatchet jobs, which paint the Ukrainian leadership as cruel, evil, or mad. One could say he’s ‘indignant’, rather than ‘resentful’.

He’s not upset though, that drones are falling close to his house. ‘What did people expect? It’s a war, you know?’ Later, he comments at length on the parade of religious icons to protect Moscow and about the satanism of the Ukrainian leadership: ‘It’s hard to tell whether they [propagandists] are telling on themselves with this or not. Certainly they are smoking a lot of good quality marijuana in the church these days’.

Or, reflecting on a TV programme about Ivan Ilyin as the ‘most popular Russian philosopher today’, notes that ‘as they say, the past really is unpredictable in this country. An openly fascist thinker [the favourite of the President] gets rammed down our throats. Who has the good fascists? Us, or the Ukrainians [despite what you read on Twitter, almost no one uses derogatory terms for Ukrainians in real life]?’

One of the underappreciated aspects of so-called ‘public opinion’ is not the capacity for people to hold contradictory opinions about it and the Russian leadership. There is very limited open talk among people with different opinions about the war and it’s quite varied: despair at destruction, ridicule of propaganda, anger at the incompetence of the army, disgust at the ignorance and indifference of most, resentment of the West’s support for Ukraine, longing about the end. But seemingly regardless, for most, their talk about the war itself is sublimated into a form of consolidation using double-meaning, humour and irony.

Boris never voted for Putin before. Like many younger people, he did not vote in 2004 (the first time anyone had the chance to judge at the ballot box the performance of Putin’s policies). He voted Right Nationalist as a kind of protest in 2008, because he liked the (duplicitous? distracting?) populist social messaging of Zhirinovsky, and because of the general dissatisfaction with the government that had made little to no progress on improving the prospects of younger people. We should note that both his parents – well educated Soviet technical intelligentsia are hardcore Putin voters – loyally they articulate that ‘there is no alternative’. However many such ‘loyalists’ are also an overdue disaggregation by observers. Some will break quite soon, I think. Many of Boris’ friends would vote Communist – or we should say ‘Left Nationalist’.

Boris didn’t vote in 2012 and observed from afar the For Fair Elections protests in Moscow. He did pay attention to things like local trash protests, strikes in the car factories locally. He signed petitions, he went to public meetings. He put up flyers made by a local group called the People’s Front that protested corruption in his town.

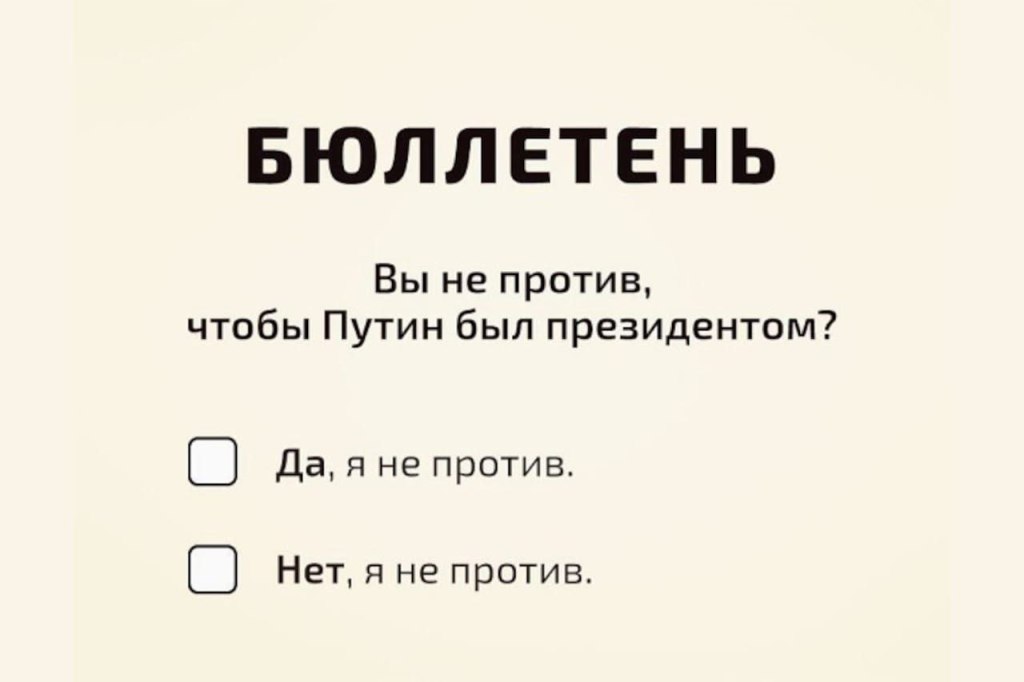

In 2018 he didn’t vote again ‘why would I? I’m not a stupid person’ – once again this ironic comment works on three levels – liberals are stupid, loyalists are stupid. Even the question reveals a tiring sense of naivety. But in 2024 he did, and for Putin. Why? Putin is the war candidate, but also the only peace candidate. Boris sent me a meme shortly after the election [actually it’s an old meme]: A ballot paper is depicted. There are two choices: ‘Are you not against Putin becoming President?’ The two boxes say: ‘Yes, I’m not against’. And ‘No, I’m not against’. There are multiple negative reasons not to be against voting for Putin.

*** [academic parts incoming]

For me, the focus once again on electoral politics, and plebiscitary indicators more generally reveals a fundamental problem with the framing of the political in Russia, the misleadingness of the term ‘authoritarianism’, and other analytical terms to describe regime types. Karine Clément in 2018 wrote that the presence of authoritarianism in places like Russia, from the perspective of ordinary people is not so obvious and almost undetectable in everyday life. She pointed to the way that civil liberty restrictions and control over the media, undeniably harsher under such regimes than in other types of state, were way less important to most people than the legitimate grievances they had with social and economic policies. As Tom Pepinsky wrote about Malaysia – ordinary and everyday authoritarianism is ‘boring and tolerable’ to the vast majority. Does that mean these same people support authoritarian rule (in the sense of giving up voice)? Absolutely not.

The authoritarian personality type was strongly critiqued in sociology forty years ago. This is an idea from the 1950s that there’s a socially significant sadomasochistic disposition that emerged and thrived in authoritarian societies and which then maintained them. However, it’s still overlooked that the ‘original’ theory of authoritarian personality was developed to explain how people in capitalist societies in the West sustained a broad submission to authority, emotional identification with leadership, belief in the naturalness of hierarchy, esp. in organizations, the heredity of natural differences between persons, the fusing of legitimate authority and tradition, and so on.

Later in the 1970s, the ‘Western’ variant was refined to refer to ‘rigid conventionalism’, where different social anxieties can be overcome by conformity. However, even supporters of the ‘type’ complain that psychologization becomes meaningless without attending to the social conditions which would produce them. Indeed, the whole psychological basis of authoritarian values when tested experimentally, tends to fail when presented with groups who hold even mild political convictions. ‘Ideological’ belief itself serves to reduce anxiety – and these may be ‘right wing’ or ‘left wing’ values. Furthermore, the development of authoritarian personality to talk about more or less ‘pathological’ types prey to demagoguery completely inverts the original concept, which, after all, was developed to explain why all of us, generally, are ‘normal’ and ‘well adjusted’ when we defer to authority, as this is how our (capitalist) society is structured and functions. Even today, to have a problem with legitimate authority is a sign of ‘maladjustment’ (Oppositional Defiant Disorder can be diagnosed in children who ‘are easily annoyed by others… excessively argue with adults’).

Back to Russia, Clément notes, perhaps even too mildly, that ‘Russians are quite critical thinkers’. She rejects stereotypical ideas about the ‘Putin majority’ and says this is partly an artefact of misinterpreting opinion polls where people answer as they are expected to. Like my own work using long-term and in-depth interviews, she finds that the vast majority are highly critical towards the state, in a sophisticated and reasoned way, in a way that connected from local and personal issues to broad social problems which affect all. ‘People make great claims against the state, and the first of them is its dependence on the oligarchy and independence from the people’.

Does the war change this? Hardly. Clément’s other point was that, by and large, people are able to exercise a sociological imagination about their own society – that it is not all about ‘Putin the tsar’. Indeed, one of the sources of support for the status quo is the realistic and relatively sophisticated conclusion that Russia is a pluralistic state with lots of competing interests and that if anything, Putin’s ability and power is quite circumscribed. And the war would only underline such a view. And this is not the same as the old saying ‘the king is good, the boyars are bad’. It’s a much more sober assessment. Clément concludes by saying that the most pertinent authoritarianism-from-below is the call for ‘more social state’, ‘a less rapacious financial elite’, and, we can add, today, ‘defence from the effects of war, and of ‘peace not on Ukrainian terms’, whether we think that is callous or not.

If there is not much ‘authoritarian’ in the values of Russians to distinguish them from the inhabitants of states where people have little access to power or voice to change things, then what is the value of the term?

***

Is Russia authoritarian because of the lack of accountability of the elite? Because elections don’t matter (actually, they do). Because the press is controlled by the regime and dissent harshly punished? Professional political scientists usually refer to the lack of free elections, but that does not generally extend to the evaluation of the responsiveness or not of leaders to populaces. This is Marlies Glasius’ argument (2018), to which he adds that the three main problems with “authoritarianism” is that

1., It’s overly focussed on elections

2., the term lacks a definition of its own subject at the same time as

3., it is narrowly attributed as a structural phenomenon of nation states.

Lack of accountability of bureaucracies, the lack of choice in elections, and the impact of globalization as a disciplining mechanism means that the differentiation between authoritarian and democratic states is overstated.

(sidebar: a Danish colleague the other day said: ‘where else but in Denmark is social conformity enforced more fiercely than by citizens themselves, with an internalized snitch culture?’ Where the state tax authority can use your mobile phone location data to check you’re paying tax right. Every day British newspapers run stories of women jailed for not paying TV licenses, disabled people forced into homelessness for being paid 30 pence too much through a state error, or, indeed, the complete untouchables that are state-sponsored corrupt oligarchs).

If Russia is now a personalized dictatorship, as many would assert, why is Putin so hesitant, distant (and even scared of being seen as responsible for) even from decision-making? Why does he appear wracked by indecision and inconsistent in his war aims? Why is the state so poor at carrying out adequately even basic logistics in the war? Further, following Glasius, to really evaluate authoritarianism in Russia we would need to look at disaggregated practices of the state structures: social policy, the courts, regional authorities.

Is accountability in these milieux sabotaged in a way that sets them apart from democratic states?

Are authorities of any kind able to dominate without redress?

Is meaningful dialogue between actor and forum prevented by formal or informal rules?

To what degree are there patterns of action embedded in institutions which infringe on the autonomy of persons?

These are much clearer definitions of authoritarian and illiberal practices, consistent over time, and which are easily documented in the Russian case. However, as Glasius points out, free and fairly elected leaders, from Modi, to Trump, and also parliamentary governments in Europe, also engage systematically in such authoritarian practices and increasingly so over time as national authority is diluted by transnational forms of power.

To turn finally to a very recent critique of authoritarianism by Adam Przeworski, he complains that existing models ignore the provision under authoritarian regimes of material and symbolic goods that people value. Przeworski says that we should pay attention to ethnographic accounts such as that of Wedeen’s work on Syria where peoples strongly denied (in the 1990s) they lived in an authoritarian regime and deployed rationalizations that were not ‘duplicitous’. Further, Przeworski argues that:

autocrats can enjoy popular support

it is difficult to interpret elections

often internal repression enjoys broad support

actual performance of economies matters and provides a real base of support

manipulation of information is never sufficient to compensate for poor performance

propaganda is an instrument of rule in every regime (including democracies)

censorship does not fundamentally provide a test of whether preferences are genuine or not.

Further, the psychological processes of people in authoritarian regimes cannot be explained by game-theories about belief. Enforced public dissimulation presents a challenge to both the regime but also to scientists in discovering ‘real’ attitudes. Further, a lá Wedeen, performance of belief might become a comfortable and natural disposition to the degree that deviance from this norm is socially disruptive but without implications for the ‘real’ attitudes of persons engaging in ritualistic performance. We get a sign here of what’s missing, the social life of authoritarianism may be more relevant and powerful than the cognitive feedback by people to all the signals around them. Many critical assessments of society and processes in Russia, as Clément notes, are not visible at all in the public sphere, and yet are universals in interviews, especially when there is less or no prompting from the researcher. The social prerequisites for positive change are always there, and people are ‘keyed’ to respond to them by human (social) nature. By the same token the desire to cleave to authority is characteristic of the most ‘democratic’ and liberal groups throughout history. The resort to social psychology models of dispositions according to a legacy of regime types is as open to criticism as it ever was.

*Obviously Boris is not a real person, but an ethnographic composite of real interlocutors.