This is the final post about Denys Gorbach’s new book on Ukraine: The Making and Unmaking of the Ukrainian Working Class. The first post is here. The second post is here.

In the previous post I focussed on how Gorbach treats populism as merely a ‘morbid symptom’ and distracting to the purpose of getting into the vibrant ‘everyday politics’ of Ukrainian cities. Gorbach early in the book shifts to ‘ordinary’ political actions and talk of Ukrainians as codetermining the scope and contours of ‘big’ politics. Using the example of the German tradition of microhistory allows Gorbach to stake a claim for the very ‘apolitical’ withdrawal from the public sphere and ‘familism’ in Ukraine and Russia as deeply political phenomena because they are a collectively shared and reflected upon. Gorbach doesn’t go quite that far here, but we can add that the often bemoaned ‘privatism’ is often misunderstood. Withdrawal provides space and time for alternative forms of organization and world-making to emerge – something I expand on in my book.

The summary of ‘moral economy’ is rather perfunctory here, although in a footnote Gorbach provides the nugget that after Tilly and Thompson, the ‘moral economy’ frame shows that claims-making from below implies the recognition by elite actors of the legitimacy of non-market-based rights. Furthermore claims are inherently political in terms of recognition – as when, for example, property laws are enforced or not enforced (e.g. as forms of recognition of customary rights among peasants and working-class folk). Wartime nationalization – even when it tends to prebendalism is also genuinely popular for the same reasons.

Gorbach gives more room to the breadth of ‘informality’ as applied to Post-Soviet politics – from Hale’s patronalism, to Matveev’s bureaucratic neopatrimonialism developing into Bonapartism. Here, Gorbach criticizes the application of Weberianism to the Ukrainian state, which can only result in seeing it as a ‘backwards’ essentialized ‘uncivilized’ polity and, indeed, plays into views that bifurcate into ‘good Ukrainian’ values (of and emanating from the West), and Bad Soviet values in the East. This will be a major target of Gorbach’s work and one that won him numerous enemies among established mainstream liberal scholars embedded in the West for whom it is beneficial to maintain this fiction.

Like in my own work, however, Gorbach insists that informality in the microscale of people’s lives is just as important as patrimonialism. This is because the informal pacts and agreements, including the invisible ones like turning a blind eye to informal employment, represent a key political arrangement of life in contemporary Russia and Ukraine. These include ‘paternalism’, a key referent of Gorbach’s book. His overview is helpful in thinking of paternalism, clientelism and patrimonialism as all nested concepts (Gorbach credits me with coining informal ‘imbrication’ but others have found this term a bit pretentious). Forms of informal obligations comprise an overall mutualist web. Importantly there are coercive, exploitative but also solidaristic, empathetic and – as I expand in my book – fictive kinship relations which may be more or less enduring and binding. As Gorbach mentions – this perspective offers a sharp critique of rational actor/methodological individualist economy and political science approaches.

Chapter Two asks: Why does awareness of inequalities and class domination not prompt workers to contest this through collective political action in Ukraine? One answer is the informal alliances of old and new elites, and at first the Ukrainian nationalist project was weak. Here we have a great breakdown on the legitimation of the ‘fatal civilizational divide’:

The failure of Ukrainian ethnic nationalism to muster its case outside its Western heartland led to its radicalization as documented by Andrew Wilson. The heterogeneous Ukrainian elites trod a fine line and their attempts to achieve social peace contributed to ongoing proverbial state weakness. Symbolic capital of the ‘national democrats’ competed with the ‘clanlike’ structural capital of the industrial cluster elites. I’m not going into detail about this part of the book, but it represents a welcome corrective to the usual blinders that pass as political history on 1990s Ukraine, notwithstanding the more impartial work done by scholars like Wilson and D’Anieri. Shout out to the use of the Marx’s ‘potatoes in a sack’ metaphor to describe the fragmented-yet-tied bloc of budget workers and city-making enterprises. What follows is a good account of the Orange Revolution, coming on the back of the rise of the resources of the ‘second-rank bourgeoisie…which grew strong enough to dare challenge the “closed access order” controlled by oligarchs’.

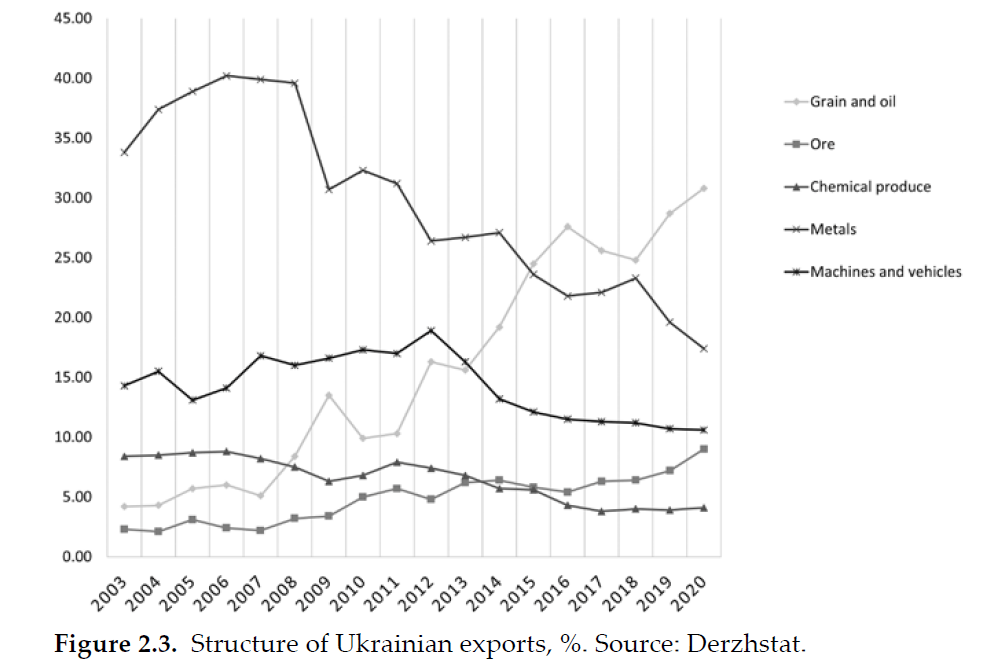

Gorbach ends this chapter by showing how political changes reflected economic ones – the failure of Euromaidan was mirrored by the downgrading of the Ukrainian economy from higher value chains to commodity export.

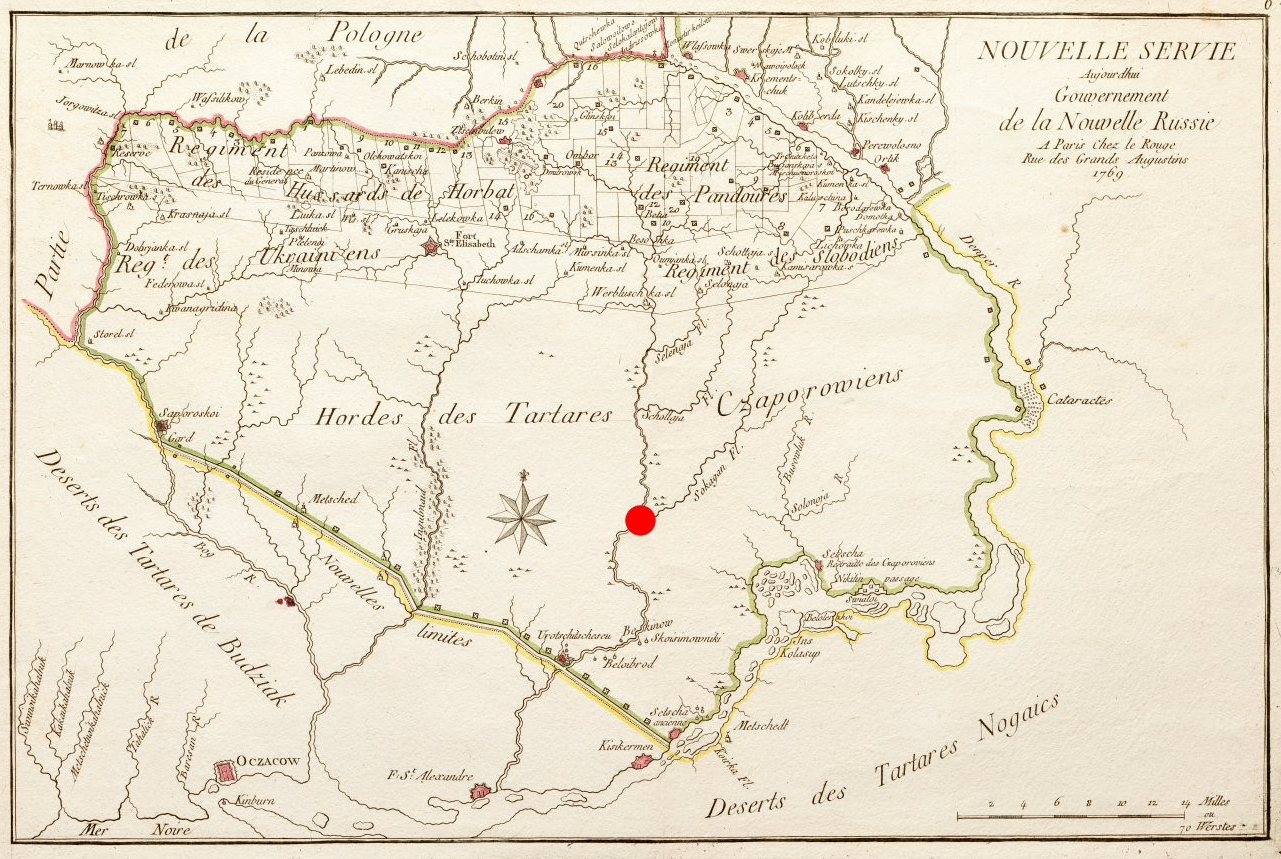

In the next chapter Gorbach masterfully recounts the actual colonial history of the steppe country around his city. In Chapter 4 he expertly uses the example of mass transit to illustrate the maintenance of moral economic regimes and the unwilling acquiescence by elites to the expectations of ordinary people. This chapter is about both the ‘privatization’ of minibuses but also the ‘resovietization’ of residual ‘public’ transit as a social good. Later Gorbach also identified three property regimes around housing: personal property where state intrusion is seen as illegitimate; private property where capital accumulation is seen as legitimate (here drawing on C. Humphrey’s work); and public property whose poor state is a result of normalized austerity. Finally, Gorbach talks about the moral economy of heating provision.

In chapter 5 – on Informality and the Workplace, Gorbach argues that instead of succumbing to anomie, Ukrainian workers implicitly gravitate towards a residual social project that owes a lot to Stalinist modernity, built upon the ultimate Fordist principles of enterprises as nodes of civilization. If this is so, the shopfloor should be a privileged fieldsite, likely to shed light on non-verbalized shared assumptions about hierarchy and social order. Of course researchers like me bemoan our marginalization as our colleagues focus on much more ‘sexy’ projects. Gorbach continues this focus in the follow chapter 6 on Paternalism in Decay. “Unable to accomplish the real subsumption of the labour process, the enterprises remain stuck in an extensive mode of economic development instead of a Toyota-like intensive mode based on technical innovations. However, such a shift would entail risks, costs and disruptions that are unacceptable to new enterprise owners. Instead of launching classic neoliberal managerial transformations, they chose to tacitly introduce new power configurations that ensured a residual paternalist consent, an undisturbed production process on the old technological and material basis, and the extremely low costs of capital upkeep. These low costs allow owners to preserve the machinery of the social wage and thereby help to protect their property rights in the case of a politico-corporate conflict.”

In Chapter 7, Gorbach looks at politicized embeddedness and disembeddedness in two profoundly different, yet quite typical business outfits in the post-Soviet city. “For Charles Tilly (2007: 78), authoritarian patronage pyramids are an important medium through which subaltern groups can be involved in macro-level political processes and discussions. This is one of the possible developments for the neo-Fordist factory regime. However, the atomized nature of these configurations in Kryvyi Rih, which remain more individualist than classic patronage politics, lead to a different kind of politicization: passive resentment, politicization of identities or striving for individual distinction.”

In Chapter 8, Gorbach shifts to a focus on everyday politics beyond the world of work, looking at strategies of self-valorization via class distinction. Here, he references Andrew Sayer, Bev Skeggs, Don Kalb, and of course Olga Shevchenko and Oleg Kharkhordin.

Chapter 9 maps Lay Virtues on the National Political Landscape. While in places like France and Britain, working classes have (more or less successfully) made use of ‘national(ist)’ or indigenous capitals to promote their marginal social position, things in Ukraine are different because of the valorization of particularized Ukrainianness after 2014 (and before).

At the end of this chapter, Gorbach makes the comparison of ‘internal’ orientalization, like that observed in Turkey and elsewhere.

In the final empirical chapter 10, Gorbach applies the findings of Nina Eliasoph’s well known ‘avoidance of politics’ work to the Ukraine context. To be ‘authentic’ in lay discourse is to devalue what is seen as ‘ideological’ as dishonest. It’s ok to be a ‘volunteer’, but it’s important to mask one’s politics. There is ‘frontstage’ avoidance of ‘politics’. There are also ‘cynics’ who have strong and informed opinions but who cultivate disengagement. All of these positions are recognizable in postsocialist contexts. As in Don Kalb’s pioneering work, this reasoning produces the ‘neo-nationalist’ outlook well-known in other contexts.

What follows is a useful discussion of the Zelenskyi phenomenon explained as a the outcome of this structural situation in Ukrainian lay politics. Gorbach is refreshingly balanced, not willing to preach to the choir, as other treatments of the ‘Zelensky effect’ have.

Subsequently, Zelensky’s channeling of the desires for ‘technopopulism’ and ‘valence populism’ (rejecting consistent ideologies in favour of vague overtures to morality, transparency, etc), sustained him nationally up the invasion in 2022, after which Zelensky successfully transitioned as a war leader.

In the last twenty or so pages, Gorbach concludes with a discussion of the ‘incomplete’ hegemonic rule in Ukraine. This is the same case as in Russia – but there we have the unambiguous move towards Bonapartism. What remains in Ukraine is the inability of national elites to claim moral leadership and the growing distance between subalterns and the institutions of representative democracy. So far, so Gramsci. But beyond that framework, Gorbach makes space for looking via the lens of Uneven and Combined Development.

And on wartime mobilization, Gorbach asks: