“Garrulous prose: a child’s mere babble. And yet a man who dribbles, the idiot… he is also without words, bereft of power, but he is still closer to talk that flows and flows away to writing which restrains itself, even if this is restraint beyond mastery.”

Maurice Blanchot – The Writing of the Disaster, 1980 [author’s translation].

I have found ChatGPT (free version) is quite good at summarising texts for me. I don’t know, but I’m guessing that the utility of it as a summarizing tool is inversely proportional to the complexity and length of the text you feed it. It works ok on shorter academic pieces, not so great on peer-reviewed articles, and not well at all on books (clearly it wants you to pay £200 for the sub version).

Yes, you can feed ChatGPT a whole academic book if you want, but I wouldn’t recommend it. I encounter numerous problems with prompts. You give it a prompt – do x, y, and z. But if the text is long and complex, the programme obfuscates, evades, and bluffs – rather like a lazy and overconfident undergraduate student (not many of those in my current institution, to be fair, and few use AI at all). Somewhere on Substack one writer said using AI was like having a ‘horde of interns’ producing text.

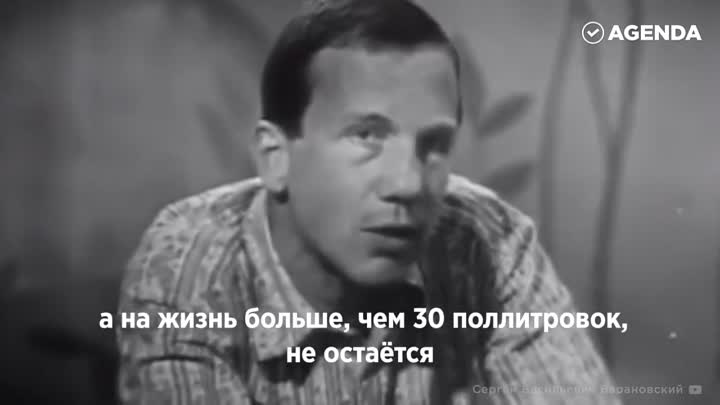

I never considered using ChatGPT to replace any of my actual writing. But I did do an experiment recently. I was asked by Riddle Russia to write a longer-than-normal piece. I think it was around 1800 words. I had around 800 down and took a break. Here’s two parts of what I wrote: the opening and a transition paragraph about.

Despite the appearance of increasing effectiveness in the Russian state’s ability to monitor economic activities within its territory and impose taxes, fees («sbory»), and levies («pobory») on them, one reassuring constant remains: the unstoppable force of the fiscal state—and now a fiscal-military state—continues to collide with an immovable object in the collective person of the Russian people themselves. As individuals and as groups, they resist and defy any final push to «enwhiten» (i.e., make visible and taxable) their incomes and wealth. More than six years ago, observers described a qualitative shift in the Russian state’s fiscal stance with the pithy slogan «People are the new oil.» Re-reading my own piece for Riddle from early 2019, it seems little has fundamentally changed.

[…]

Poor auditing and opaque ownership of such systems are designed as part of the sistema of extravagant economic rents. As it was with Platon – the road pricing system for heavy goods vehicles which Alexei Navalny revealed in 2015 as essentially a scheme for further enriching insiders – the actual effectiveness of this fee-collection system to the state (in terms of providing revenue for investment in roads) was shown to be minimal. Subsequently, it has delivered much value to its insider controllers while it’s contribution to the Russian road fund has been modest over more than ten years of operation (approximately $3bn – less than a year’s spending on roads by the state). Road building and construction – which can cost up to $30m per mile in Moscow (in expensive Germany, highway construction costs around half that) – are even more fertile ground for skimming and kickbacks, with frequent corruption cases and audit problems even published in the Russian press

I pasted the text above and what else I had written into Scholar ChatGPT and asked it to “Continue the report that follows this prompt – complete it with details and links to Russian-language online sources using the same style and argumentation. Incorporate evidence from the sources you find in support of the argument”

I skimmed the results – part of which follow:

Wartime Economic Informality as a Safety Valve

Despite repeated attempts to formalize economic life, the wartime economy has deepened informality in everyday survival strategies. According to estimates by the Higher School of Economics, up to 33–35% of Russian households’ income in 2023 remained “неучтённым” (unaccounted), up from 27% in 2019 (НИУ ВШЭ, 2023). Researchers like Natalia Akindinova emphasize that informal income has become “a crucial buffer in an era of mobilization and inflation.”

Regional press and outlets like РБК describe how self-employed “самозанятые” workers—drivers, delivery couriers, online tutors—have grown rapidly, reaching 8.3 million people by mid-2024 (РБК, 2024). Yet most of these operate in “grey” modes, underreporting or omitting real turnover. This semi-tolerated opacity allows low-income Russians to maintain consumption levels despite stagnant wages and military tax surcharges introduced through indirect levies (fuel, excise, and VAT)

It all looked really helpful. I wouldn’t use the text, I told myself [a warning sign!], but the links would make it a lot easier to finish my assignment. The Chatbot helpfully presented my requested sources and they looked perfect to me:

Cited Russian-Language Sources:

- НИУ ВШЭ (2023). Теневая экономика в условиях санкций. https://publications.hse.ru/articles/847392460

- РБК (2024). Рост числа самозанятых и доля серого дохода. https://www.rbc.ru/economics/18/05/2024/6648f3729a7947ed8e23d11a

- Ведомости (2024). Параллельный импорт как новая норма торговли. https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2024/02/19/967498-parallelnie-importi

- Коммерсантъ (2023). Серый импорт и экономика военного времени. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6059428

- РБК (2023). Проверка эффективности системы «Платон». https://www.rbc.ru/business/27/07/2023/64c26f4f9a79475c8f7f1132

- Meduza (2024). Война выгодна своим: экономические ренты в инфраструктуре. https://meduza.io/feature/2024/04/29/voyna-vygodna-svoim

- Коммерсантъ (2023). Теневая экономика как элемент устойчивости. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6100234

- Хазин, М. (2023). Параллельный импорт как форма народного протекционизма. https://khazin.ru

However, a few days later, I tried the links – they’re all ‘hallucinations’ – none of them can be traced to a real-existing source. But they are all so plausible. Especially the academic ones linked to Higher School of Economics, Moscow. One aspect that led me to feel initially feel confident that ChatGPT had given me genuine links and sources and saved me time was that in the text it produced it cited real researchers who actually do work on these topics. For example, the generated text said, “Researchers like Natalia Akindinova emphasize that informal income has become “a crucial buffer in an era of mobilization and inflation.”” This appeared to chime with the kind of topics this Moscow researcher works on. Except that it too, along with all the citations in the ChatGPT document are fabrications.

Overall, the time I spent using ChatGPT for this assignment reduced my productivity – something others have encountered. In summarizing some short texts, I still think it has uses in increasing productivity. But here’s the catch, the temptation to trust it is going to be too high to the time-poor: those under-pressure writers and researchers. Or the lazy – like me. Or the dishonest.

I also think it’s underestimated how many researchers and academics just don’t really enjoy (or value) writing and will go to lengths to avoid it. Added to that is the capture of the academy by the neoliberal concept of value and production (your worth as a scientist is measured by individualized metrics and then expressed financially). Very few people are writing papers because they really want to. Plagiarism is rife already (i recently reviewed an academy grant application that had plagiarised my work and I’m an extremely marginal researcher – think about that!). Many publications are ghost-written for profit. It was already the case that ‘signal detection’ was a problem in academic writing – where the volume-to-noise ratio made detecting worthwhile papers difficult. Someone recently remarked: “bad papers now look like good papers” but has this never not been true?