A new book by Marlene Laruelle seeks to answer the first question, if not the second. Ideology and Meaning-making Under the Putin Regime is just under 400 pages and is somewhat of a departure from the fashion in US-published books for slim volumes. A few people asked me to write a review of it after I mentioned it previously, but this post is not a real review, but just some reflections based on my interest in criticizing approaches to understanding ‘late Putinism’ that rely too heavily on coherent ideological explanations. Having said that, Laruelle is one of the scholars most careful and scrupulous in her research.

At the outset, Laruelle asks: ‘How did the Russo-Ukrainian war become possible, and what role did ideology play in enabling it?’ The Introduction goes on to argue that the ‘Russian regime does offer an ideological construction that has internal plausibility and coherence’. For Laruelle, and perhaps most political scientists, the regime uses three mechanisms to ensure hegemony: material, ideational , and repressive. The first two are ‘cocreational’ – meaning that people link prosperity with the general will of the regime and identify with it. At the same time, Laruelle admits, the vast majority of Russians sense a lack of a state ideology. Her jobs then is to try to reconstruct something resembling a coherent set of beliefs or a world view and show how it is shaped by the elite in a feedback system with intellectuals, the outside world, imagined history, and ‘the people’.

But before doing that, her intro is really effective at criticizing existing approaches – showing that they severely neglect the ‘ideational’. She confidently dispatches what we can call the ‘kleptocracy’, ’empty propaganda’, ‘totalitarian’ approaches. At the same time, Laruelle sets herself some limits – ideology is about meaning-making and not propaganda, and it’s not about doctrine but worldview. Most importantly, ideology is aggregated from multiple repertoires and may not always/even inform policy.

The rest of the book is smartly structured in four parts. Reordering Ideology; Learning and Unlearning the West; Russia’s Counterrevolution; Russia’s Geoimaginaries.

Part 1 tries to get away from the idea of ideology as imposed by coherent actors from above while emphasizing the general tendency of state ideologues to present the current social order as ‘valid’ and irreplaceable. Three elements of regime doxa were formed in the 1990s: anti-collapse; normative great power recognition; state over (and encompassing) nation. This develops into five strategic metanarratives which then dictate the content of much public speech: Russia as a civilization-state, Russia as katechon (holding back the antichrist), as anticolonial force, as antifascist power, as defender of traditional values. Laruelle argues that despite the ‘chaos’ of ideologemes one encounters, there is a coherence to public speech that adheres to a mental apparatus with ‘roots’ in these narratives (p.19).

All the ‘topoi’ that ever enter lay talk, like ‘Gayropa’, or ‘collective West’, can be traced back to the core metanarratives and then core beliefs. ‘Indeed, as in jazz, there is an established common theme or point, but each authorized player is allowed to improvise at will… There is both ideological opportunism… and stability in the core set of beliefs.’ (23) Perhaps feeling that this is altogether too neat, after some analysis of individual worldviews at the top of the elite, Laruelle acknowledges that various issues still can’t be explained by this framing alone. There are, after all, lots of intervening institutions and actors. ‘It is challenging to to decipher what is genuine cocreation from what is cueing’ (28), Laruelle remarks, before reminding us that very few security elites favoured an aggressive Ukraine policy before the war. Part of the answer is the tendency of authoritarian neoliberalism to produce ideological entrepreneurship, of which Z-patriotism is just the latest example. However, the regime itself is not the addressee here: ‘a vision of Russia that emerged in lived experience by Putin’s inner circles and more broadly the establishment… looked for intellectual soil and a better-articulated doctrine to justify and nurture itself.’ (37).

Part 2 traces the rejection of liberal internationalism since 2000. Analysing the use of the word ‘liberal’ in Putin’s speeches, Laruelle argues that ‘his self-presentation is purely situational, if not opportunistic or cynical… and [while he] has never totally abandoned references to universal values, the shift from supporting liberalism… to denouncing it wholesale has been a major change.’ From here its a short walk (to 2022) to an idea of recovering a ‘first modernity’ – an idea that ‘there exists a true Western heritage rooted in a rejection of some forms of modernity’ (92) and in this sense, Russia borrows from the US culture wars significantly. Partly because of this weak and reactive form of antiliberalism, ‘there is no consensus among the Russian establishment regarding Russia’s relationship to Europe identity-wise’ (96).

This Part also covers Byzantium and the ‘Pontic power’ shift after 2008 but which had weakened by 2022. There follows a chapter on patriotism as state-centrism – the idea that the only soveriengn actor can be the state. Over and above the usual argument about how empire, statism and statehood support each other, Laruelle discusses the discourse of ‘historical continuity’ (preemstvennost).

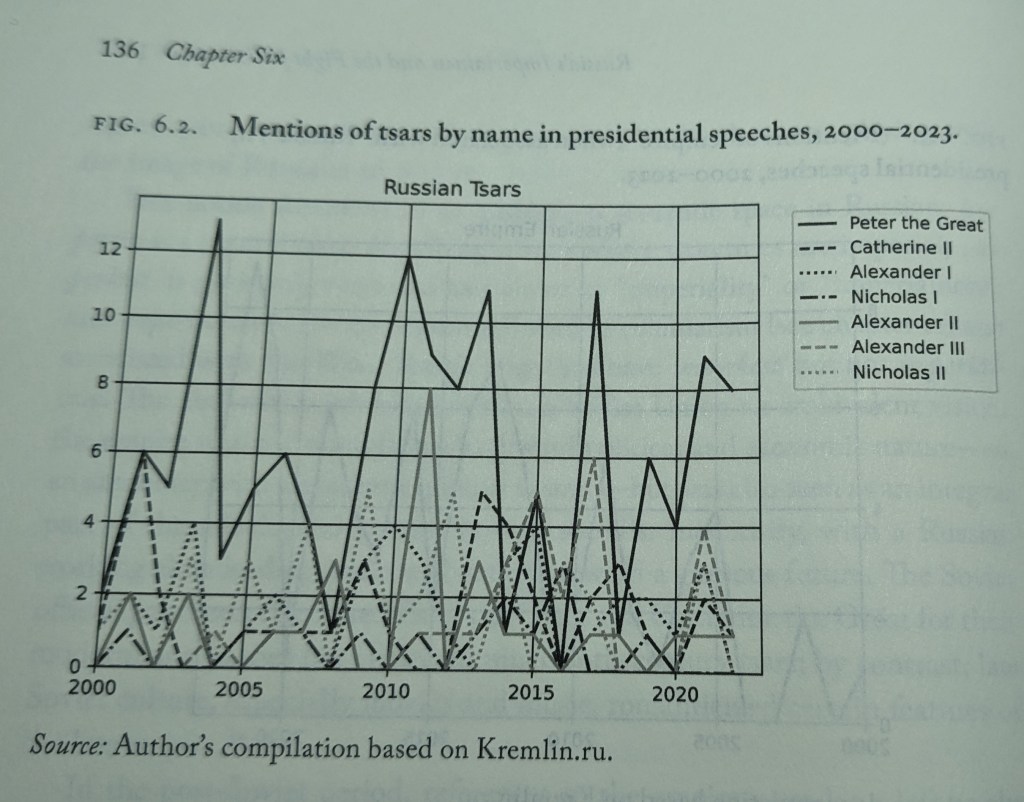

Throughout the book, there are author-calculated graphs of the rise or variation in the mentions of particular words. For example, on p. 113 we witness a striking rise since 2000 of the use of the term ‘patriotism’ in presidential speeches. Sometimes these figures speak for themselves and help support the main argument, but in other cases the ‘data’ looks noisy and too Putin-centric. On patriotism, it’s striking that Laruelle meticulously documents the spectacular and discursive promotion of pro-patriotic symbols and spaces, but, like the regime itself, emphasizes the closure of narratives, the narrowing of what can count as patriotism and how little ‘content’ the ‘spatial imaginaries’ and ‘uses of the past’ have room for. A genuinely productive and mobilizing deployment of Stalin, WWII, Lenin, Brezhnev is impossible because of the timidity and incoherence of the regime, while the celebration of Russia’s environmental diversity, modernization and ‘valorization of territory’, are notable for what they omit or would appear absurd in proposing.

Similarly, the reconstruction of Russia’s ‘Imperialness’ in the next chapter shows the regime is not without ambiguities and is even half-hearted. For example, rehabilitation of White ideology (the anti-Bolsheviks in the Civil War) is limited to the cultural sphere. Fully embracing it would mean devaluing useful elements of the Soviet heritage. Putin here emerges as a bit at odds with the rest of the elite – much more anti-Bolshevik and more pro-Tsardom. Laruelle gives us a neat overview of how Putin and Medvedev have referred to tsars, but this is a good example of the messy data – the graph is just a series of ups and downs, even allowing for the clear devotion of Putin to Peter the Great (136). This chapter also deals with the very real revival of antisemitism by regime insiders and the extreme anti-Ukrainianism of Timofey Sergeytsev, though none of the radical voices are quoted in the new ideological school textbook sponsored by the regime (144).

Part 3 opens with a chapter on Russian civilization as rejecting Western Universalism. Cue a journey through Spengler, Toynbee, Huntington, Eisenstadt, von Herder and a brief reiteration of the nineteenth-century Slavophilism and then the Soviet rehabilitation of Spengler through to the late Soviet and post-Soviet influence of Gumilev, Panarin and the replacement of Marxism-Leninism by ‘kulturologiia’ – an essentialist new superstructure explaining world history to Russian students. For example, A. Panarin links ‘Russia’s messianism to being a global safeguard of polycentrism: by its very existence, Russia demonstrates that the West is not the sole driving force of development’ (156). Here we get also a reiteration of Laruelle’s argument that ‘Russianness’ has been detached from ethnonationalism by Putin successfully, and a short discussion of three versions of Islamic civilizationalism that compete within Russia today (Slavic-Turkic fusion; Volga-Ural centrism; eclectic Kadyrovist loyalist conservatism).

Chapter 8 is perhaps the key chapter in some ways to the book – on Conservatism. Three sources inform today’s version: tsarist era, Soviet ‘social conservatism’, and the interest in ‘morality’ from the 1990s. Here I feel there are some stretches, or at least some grounds for more debate – as any of the three ‘sources’ here remain obviously open to interpretation. Nonetheless, Laruelle is willing to back up her argument with plenty of evidence, noting, for example, that the moral aspect of liberalism in the 1990s often goes unnoticed (173). Once again, in this chapter, a reader might get the impression that the resort to quantification of terms like ‘traditional values’ in speeches has little to add to the rich scholarship of the author.

Mentions of ‘tradition’ are pretty stable since 2005 (or rather the standard deviation increases for a while and then reverts to a norm when it comes to words like ‘spirituality’ – which is a notoriously empty signifier for Putin). We get intimations of the slippery, unconvincing embracing of conservatism when the author reveals nuggets like the fact that there is hardly any investment by the state in intellectual research on conservatism (186). This leads Laruelle to note that those conservative intellectual entrepreneurs who tried to work with the Presidential Administration were to be disappointed.

This explains why so many ‘entrepreneurs’ like Kholmogorov became more reactionary – not because of an alignment with the regime, but because of their frustration with it. Thus, it is surprising when Laruelle ends by arguing that conservatism really is the ideological backbone of the regime, and indeed, that it is a national conservative one, albeit that it is a national state form of conservatism. Coming away from this chapter I understood that a vague form of conservatism is an organic part of intellectual history in Russia and has a social content, but that has had almost no contribution to policy output directly (beyond contradictory tokenistic lawmaking by the ‘rabid printer’ that is the state Duma). On these terms one might argue that a country like Denmark or the UK is more consistently conservative – especially in terms of what the book proposes as a ‘cocreated’ hegemonic ideology.

In Chapter 9, Laruelle tackles the subject of Katechon as part of a reactionary tradition in Russia of millenarianism and eschatology. Russia, after Maria Engström, is the ‘gatekeeper of chaos’. In this logic, the Ukraine war could be seen as part of a Reconquista. Nuclear Orthodoxy, Soviet imperialism, mystical Stalinism, and my personal favourite – the legend of the City of Kitezh (which can autarkically submerge itself in the heartland to hide from the hostile neighbouring territories) all rub shoulders in a bewildering postmodern eclectic blend of religious inspiration. ‘Teach us to breathe under the water’, never sounded so apt.

In Chapter 10, the scholarly fashionable idea of identity as spatial imaginary gets a comprehensive treatment. Laruelle here reissues her own contribution: Russia as fertile ground for geographical metanarratives (212). Russia is (and can only be) Great because it is big and has expanded a lot. Eurasian destiny as teleology. Without empire, there’s no Great Power status. Cultural and political boundaries do not overlap with state borders – Franck Billé’s idea of ‘auratic bodies’.

But the notion of Eurasia remains horribly elastic and fuzzy, as Laruelle points out herself. A common destiny led by Russia? (remarkable to think about this given the admission by most Russians that they are completely dependent on the whim of China now). Eurasia as civilizational project which differs or competes from Euroatlantic ones (again, an empty signifier)? The book does show that at least performatively, Putin likes to play around with the the term ‘Euro-Asian’ from 2012 onwards. However, characteristic of his improvisation, this discourse drops off from 2020 sharply, perhaps because of the failure of the Eurasian Union. By the end of the chapter, the author admits to ‘numerous semantic gaps. No official text about the Eurasian Union mentions Eurasianism as an ideology’ (230). And the ‘founding fathers’ of Eurasianism enjoy cultural, but not political, prestige (with the exception of Gumilev, perhaps).

Because this is a v. long post already, I will skip the final Russian World and Anticolonialism chapters, though they are just as informative and well-researched.

In the conclusion Laruelle argues that Russia has moved towards a much more rigid ideological structure and has an official ideology (265), but at least to this reader, the book, with its repetition of the terms ‘repertoires’ and ‘plasticity’, seems to argue for something different – perhaps the word ‘ideology’ is inadequate here. Can an official ideology be entirely negative – based on resistance to the West, and promoting an all-powerful state? As Laruelle notes – Russian efforts to project soft-power have failed and ‘the state’s survival remains the main objective of the regime, and acquired territories are subordinated to this state-centric strategy more than having a value in themselves’ (266).

‘Typologizing … the Putin regime may be morally reassuring, but it does not automatically provide a heuristic approach for scholarship if the typology is taken at face value and not itself interrogated’ (269). Should we talk about Putinism? Only in so far as a collective Putinism expresses how all these historically determined discourses get more or less traction over time. ‘War Putinism was only one of the possible options of early Putinism…Ideology matters when it reinforces strategic goals, but not enough to force a decision solely on this basis’ (272). For Laruelle, the war forces the blending of formerly disunited repertoires – soveriengty, civilization, conservatism, traditional values, etc. ‘The war has provided internal coherence to this ideological puzzle’ (273). Manufacturing consent has its limits, but it is aided by depoliticization, dissociation, ‘consentful’ discontent, ideological passivity, and a shared ‘zeitgeist’ with the regime: that Russian society is superior (‘healthier’) to the West. Thus, in conclusion, Laruelle sides with quantitative surveyors in proposing a relatively coherent national-conservative majority, while leaving the future open to alternative reinventions such as cooperation with the West, or an ‘Asian’ model like Singapore, or even an illiberal grassroots democracy.

As regular readers might surmise there’s a lot here I both agree with and disagree with, but for anyone wanting a survey of all the genealogies and diversities of Russian national-conservatism, this book will not be found wanting.