This will be a short review (well, actually not short) of some Russian media commentary (A. Pliushev, E. Schulmann, N. Zubarevich) and my reactions. If you think this kind of post is useful, let me know. It is often the case that informed discussion in Russian language on YouTube never really cuts through to anglophone audiences for Russia content. I don’t ‘endorse’ the persons or positions of any of these public intellectuals and journalists, but this kind of content is important for non-Russian speakers to get access to.

Virtual Autocracy?

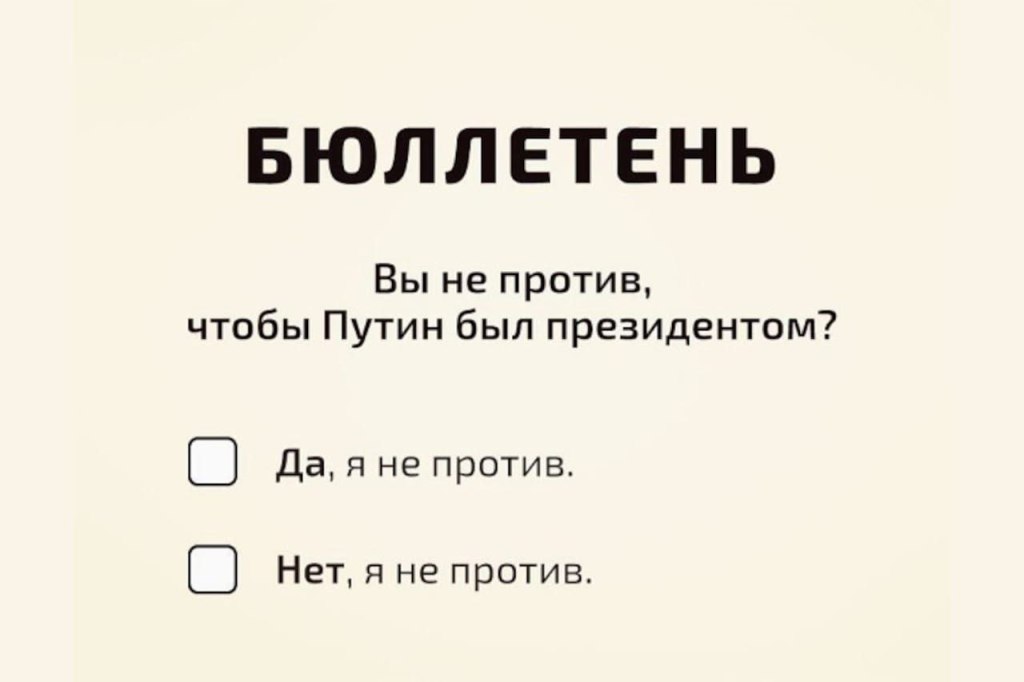

At the beginning of September there were simultaneous elections of various kinds throughout Russia. The results were not very interesting but the strong push to ‘virtualize’ voting as much as possible is. Why not continue to rely on the physical and very visible power expressed in falsifying actual ballot papers and busing in people to vote on pain of losing benefits? The resort to a virtual electoral autocracy shows the authorities have a good idea of their genuine unpopularity and the continuing risks, even now, of all kinds of upsets. Not only that, they also understand the advantages of digitized authoritarianism (I’m hoping to do a big write up of this soon). You can geolocate voters in the app they use and this exerts a coercive power of its own.

But, as Ekaterina Schulmann pointed out in her review of the elections, getting rid of the spectacular in-person falsification reduces two powerful indirect effects: the visible demonstration of loyalty by voters to the state (which goes back to Soviet times) and which speaks to the main reason for elections in autocracies – the idea that legitimization still needs a public audience. Secondly, in the Russian case, virtualization means that the army of state workers – mainly schoolteachers and local council employees– are ‘let off the hook’ they’d previously been sat on: being implicated as ‘hostages’ in the falsification process as counters and electoral polling workers. Cutting out the middleman is interesting and perhaps reveals a real buy-in among the elite to the idea of “full-fat digital autocracy” maintained by technocratic management of populations. But, thinking sociologically, normalization of involving the morally-important category of teachers in illegal compliance with the diktats was the strongest spectacular effect of Putinism. Here, I’m also reminded of the big conflicts even now between parents and teachers over the disliked patriotic education lessons, with the latter stuck in the middle and largely unhappy at carrying out this task (more on this in my forthcoming book).

The election also revealed other indirect information about the emerging post-2022 Putinism ‘flavour’. There’s no sign of the much-expected ‘veteran-politician’ wave. Special Mill Op vets are not getting elected positions – many supposed examples of this in the media are just low-level bureaucrats who had to go to the ‘contact zone’ (frontline) to exculpate some disgrace and then came back. A big thing to watch for in 2025 also related to the war is the fact that on paper, the proportion of the national budget devoted to defence is due to fall according to the Finance Ministry. Watch this space.

The non-appearance of the Great Russian Firewall

On media use, Alexander Pliushev looked into VPN usage, and estimated that around 50% of internet users in Russia are now forced to use these services to access content, but probably not because they’re looking for subversive information. But there are plans afoot to root out VPN usage, along with the slow-down on services like YouTube. However, it is estimated to take years to root out VPNs, and this doesn’t take into account measures to develop new forms of avoiding blocks. Pliushev feels confident in this because while number of views of his content fell a lot from Russia, the overall picture is unchanged – meaning people just switching to VPNs. He should know: the ex-Moscow Echo journo has an audience of 300k viewers on Bild, and 700k viewers on his own channel. Already we see the emergence of IT service providers of ‘partisan’ packages to customers which improve the speed of YouTube.

Television as domestic wallpaper

A good accompanying piece on TV and media use came out in July by Denis Volkov of Levada. In this piece he claims TV as a source of information is still really important, and I have some questions about that. It’s true, as he says, that the TV news is always on in the background of people’s homes, but other sources have reported that TV ad revenue has ‘followed’ the decline in audiences since 2022 because people are generally turned off by the very visible war coverage on main channels. Indeed, at one channel I know intimately, worker’s contracts are not being renewed and people are not getting the pay increases they expect. What’s more interesting about the Volkov piece is how rapidly the coverage of social media has changed – the rise in Telegram: readers of ‘channels’ there (mainly news and current affairs) has gone from 1% to 25% of the population since 2019. This is a sobering reminder to be cautious about state’s capacity to control informational dispersal. The unparalleled rise in the onlineness of Russian means we should also avoid too many historical parallels (Vietnam war, Afghanistan, WWI, WWII). We really do live in a different age.

There’s a lot I don’t agree with in the Volkov piece, but it’s worth a read. As I’ve frequently written here, if you’re attentive then stuff like this from Levada people reveals deep-seated ideological assumptions about Russian society that can surely be questioned. I don’t agree with his insistence on uncritical media consumption and the simplistic ideas about how TV shapes views. Nonetheless we get more interesting points – like that 28% of people don’t watch TV at all, that the audience for Twitter and Facebook is tiny at 2%. Late in the article we get the statement that the share of television as a news source fell by 33% in the last 15 years, somewhat undercutting Volkov’s insistence on the relevance of TV as a regime-population conduit for propaganda.

“It’s the regional economy, stupid!”

Moving on to Natalya Zubarevich’s frequent and detailed online talks (with Maxim Kurnikov here in mid-Sept) about regional economy and demography in Russia, she lets slip some interesting observations beyond her usual scrupulous (and self-censoring) focus on the ‘facts and figures’ from official documents. She talks about how noticeable it is that in military recruitment in Moscow there are few young faces and a preponderance of ethnic minorities. She talks about the current ‘hostile migration environment’ led to harassment of gig workers in taxi-apps (Yandex). But not due to war-recruitment pressure, rather to increase bureaucratic monitoring of taxi drivers in the capital, reiterating the point above about the government staking more on digital control. She says we have good evidence for this squeeze because of the rising visibility of Kyrgyz drivers for whom there are fewer migration hurdles. (Gig workers from Kyrgyzstan represent a case study about the gig-economy in my forthcoming book).

Zubarevich makes the point that low paid blue-collar workers are being sucked dry by the war machine. If we accept the national soldier replacement rate target is 30,000 recruits a month then yearly Russia is losing around 1% of the available male workforce – but it hits harder in logistics, warehousing, manufacturing, and so on and hardly at all in, for example, local government. She also provides good examples of agency within the state: where the Agriministry was able to get the enlistment offices to back off men who work as mechanics for farms.

Some criticise Zubarevich for her insistence on talking only about published statistics. Here, without openly saying it, she pours cold water on the idea of sustained income rises keeping pace with inflation. She doesn’t believe the figures of high annual percentage rises in salaries as sustained or ‘real’ (net effects). She also points to clear slowing in wage inflation in 2024. This then allows her to demolish part of the military Keynesianism argument. Low incomes have seen big increases but from very low base starting points (an apple plus an apple is two apples for the blue-collars; but the people in white collar jobs were already earning 10 apples. If you given them one more apple do the blue-collars feel less unequal?). Periphery growth (in regions including war factory locales) is not significant because it does not begin to affect the overall level of inequality in society.

What conclusions do we draw from Zubarevich’s dry statistical analysis? It’s a paradox that in Russia’s ‘necrotopia’, where multiples of annual wages can be earned for surplus people by offering themselves as victims to the death machine, the overall value of blue-collar labour has increased to a degree that alters the bargaining power of workers who remain uninvolved directly in the business of dying for cash. Nonetheless, productivity, whether in military or other parts of the economy has not increased at all because of human and technological limits. You can introduce another shift, pay people 30% more, but that doesn’t mean that the output/hour of tanks, or washing machines or nuts and bolts (another case study in my book) goes up. Zubarevich comes around to a quite conservative position. It might seem like the war has the potential to break a pattern of decades of very high income inequality and massive underpayment of ‘productive’ people, but the inflationary effects of war are already bringing the pendulum back to ‘normality’. She also reminds us that inflation and the isolation of the Russian economy mean that ‘veteran’ incomes will never have significant levelling effects on inequality either.

On the Russian Defence Ministry shake out

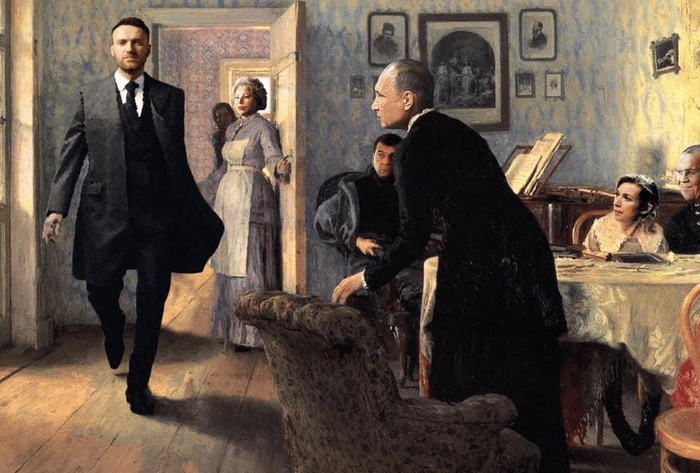

Back to Schulmann in conversation here with Temur Umarov. The purges in the Defence Ministry are like the Malenkov-Khrushchev pact after Stalin’s death. A new deal: not only will you not be physically exterminated in the war-of-all-against-all where there are no institutions to regulate political life, we won’t punish your relatives either.

What’s happening in the Defence Ministry is a Putin-style purge: not based on ideology, one could even call them ‘nihilistic arrests’, supporting the idea of nihilism at the heart of Putinism. And as Schulman says, this only serves to destroy any idea of narrative structure to the war aims. Umarov: it is Stalinist in the one sense that it’s a structural process of social mobility: unblocking of avenues for advancement for sub-elites. This should also give us some ideas about ‘where we are’ in the maturing or even autumnal days of this regime. Are these arrests signs of sub-elite impatience for more radical regime transition (in terms of personnel, not necessarily politically)? Stalin-Khrushchev-Brezhnev? It is probably a mistake to interpret this in terms of anyone thinking that these new faces will be ‘better’ at the job of war. Schulmann asks: are these repressions for the war, or repression instead of war? What she means is that instead of the fantasy that the overturn of corrupt military elites will allow real competence and patriotic leaders from the ‘ranks’ to emerge, in reality we just get new clients and relatives of those still at the top.

Schulmann reveals perhaps more than usual in this ‘academic’ talk setting. Her view now is that the core hawkish elite really did want to go to war in 2020 and only Covid intervened. There was a test run of an alternative ‘institutionalization’ of elite wealth and status transference in the 2020 constitutional amendment. It was a groping towards cementing the ‘rules of the game’ to lock in elite self-reproduction. But in reality few could believe that this this compact would survive Putin. For Schulmann the rejection of this compact as unworkable, and subsequent turn to war as a ‘solution’ for the problems of elite consolidation really, shows the genuine narrowness of political imagination in Russia – no one really believes institutionalization is possible, and that even in the West it must also somehow be a ‘show’ or ‘fake’.

Russians: We don’t know what the war is for

One final nugget is the latest Russian Academy of Sciences’ sociology centre monitoring report from April 2024. There are many surprises, but one stat stands out. People are asked, towards the end of a questionnaire containing sometimes absurdly slanted questions, about the Special Military Operations’ “solution”. They don’t get to choose their own answer, only pre-selected ‘options’.

Comparing the mid 2022 version with mid-2024, the results are interesting:

What should be the aim of the SMO on demilitarization of Ukraine and liberation from nationalists?

Liberate all Ukraine: 2022: 26%, 2024: 16%

Liberate Donbas: 2022: 21%, 2024: 19%

Liberate ‘Malorossiia’: 2022: 18%, 2024: 20%

Liberate UA minus west: 2022: 14%, 2024: 20%

Other opinion: 2022: 3%, 2024: 1%

Difficult to answer: 2022: 18%, 2024: 25%

There we have it: the plurality are ‘don’t knows’. The ‘other opinion’ includes the possible selections, destroy fascism, destroy Nazism, end Ukraine as a state, destroy Banderism, preserve Russian territory, keeping only Crimea. (A bit ambiguously worded, that. Did they mean to write: ‘keep Ukraine as it was, but leave Crimea to Russia?) Who knows. As my interlocutor writes: likely this document was heavily ‘curated’ and then the sociologists tried to rewrite it to make sense while not annoying the powers-that-be. Imagine a guy in epaulettes standing behind the bozo writing the report.