In a wide-ranging interview for Die Zeit a few weeks ago I said: ‘for most, a national catastrophe seems more conceivable than that Russia could succeed in subjugating Ukraine. The prevailing mood is pessimism.’ In terms of parsimonious analysis, this is probably the most anyone studying Russia can offer.

Outside of Russia however, it’s noticeable how this analysis is not enough for students, colleagues, and media and public alike. After four years of war we are all supposed to have a definitive take. Things must be moving, according to some established rules of causality, in a particular direction. But a marker in time is arbitrary. There’s nothing about the passing of four years that gives much more insight than six months ago, or six months hence. There’s very little value in giving an assessment of where we are, or where we are going. Furthermore, the temptation to stock take, while useful, often leads off in the direction of causal inference and prediction.

But the invasion of Ukraine, like the collapse of the USSR, should remind us that social sciences are not predictive. And this has been just as true of the part of the social science spectrum that claims the most “scientific” of approaches – economics. While there was a good lot of literature that said sanctions and embargoes could have effects on belligerents, that same literature also pointed out that this was only likely to work in contexts of massive and overwhelming differences in power.

Nonetheless, after four years, I still think it’s ‘the economy stupid’ that will make a difference. This was discussed in our recent Russia Unfiltered podcast where I made the point that Russia has far fewer resources overall than even Europe alone. The ‘economic’ argument, also offers – I think – a middle way between the rock of the realists, and the hard place of hawks that Seva Gunitsky outlined in January 2022. Incrementally increasing economic pain might make the supposition – that the Russian government cares much more about the outcome of the conflict, and is therefore able to pay much more for it and raise the stakes – irrelevant if the coming real stagnation of the Russian economy becomes visible and felt by everyone (and indeed, it will expose political fractures precisely because it will also reveal who has profited handsomely, and who is cynically protected from pain).

French historian Marc Bloch argued that the most meaningful comparisons are those which are maximally similar and consequentially different in only a few respects. Comparative study might very well be more meaningful within regions like the former Soviet one than across them. This is why most of the best work on the war to date has avoided historical and political parallels that are too distant from the immediate context. Nonetheless, one that I risked making myself – a comparison between the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s and the Russo-Ukraine war, perhaps is still helpful for one good reason: its lesson about unpredictability due to the intractable process of long regional wars.

Iran-Iraq showed that outcomes were not at all predictable based on available evidence; outside interventions had effects but not immediately or in direct causative ways. The relative weight of the intervention of individuals and elites changed multiple times (and like in many wars, elites’ non-decisions were sometimes more important). And, to go against one of the points I made earlier about the danger of historical parallels, Iran-Iraq’s outcome was the strengthening through war of both countries’ militaristically-minded core elites. With terrible consequences shorter and longer term for their societies and their prior limited pluralisms.

It might be professionally satisfying for me to say ‘I told you so’ in response to Meduza’s new investigation that shows that Russian battlefield losses are severe but not half as bad as Western intelligence agencies are reporting. Well, I did tell you so, repeatedly – pointing out that because of a lack of professional analysis, Western agencies were mainly just repeating Ukrainian figures which were understandably propaganda. However, even if it were true that losses were much higher it would not change the calculus that it’s the relationship between money, interest rates, exchange rates and oil prices that run the war, not bodies. Bottom line: for Russia war mortgages the state. But sometimes it does so in a way that is unsustainable for non-core powers, of which Russia is a classic peripheral player vulnerable to numerous economic forces beyond its control.

So, beyond this perhaps limited historical comparison, what can I say I got right? Looking back at some of the posts on this site since 2022, a few stand out. There’s my reading of Snyder and Laruelle from May 2022, where the former argues that Russia is fascist and the latter retorts that Putin is not even Pinochet. In the same piece I emphasise the axiomatical political instincts of the regime remain focussed depoliticization and demobilization, but that of course this also creates major weaknesses in governance during wartime.

In October 2022 I wrote about the Donbasification of Russia itself, using the metaphor ‘North Korea-lite’ to show how historically, the erosion of norms and laws in occupied territories and conflicts has a boomerang effect on the imperial core. Little has changed in my assessment and in any case this is hardly an original idea. The problem really comes if the conflict ends, because the erosion of the rule of law, the high corruption within the MIC, and the need to scapegoat insiders, particularly in the security and economic elite only intensifies after a peace is signed.

In April 2022 I returned to my pre-war predictions as to what would happen in Russia and found them overall to be sound. One thing I didn’t anticipate because of my own blinders was how effective the politics of fear would become:

Continuation of the ‘politics of fear’. Again, I underestimated how fast Putin would clamp down and allow the narrative of internal enemies and traitors to justify all kinds of score-settling. I also did not foresee significant emigration by the upper-middle class. Fascism lite? Bonapartism? Others (Greg Yudin here) are very quick to go down those roads. I think for the time being I’ll stick with my version of authoritarian statism inspired by reading Nicos Poulantzas. “the ‘masses’ are not integrated (partly because politics is replaced by a single party centre), and pernicious networks like security interests are ‘crystalized’ in a permanent structure in parallel to the official state”.

In that same post I also refined a little my ideas about defensive consolidation which later appeared in a further revised form in my 2025 book:

Defensive consolidation involves magical thinking and denial… It involves a cleaving to authority (not necessarily the government, but your boss, your factory, your town leader), not out of loyalty or enthusiasm…The more Russians cleave to authority the more they are effectively ‘admitting’ to themselves how bad things really are.

DC is something of a ‘sweaty concept’ – I keep reframing it because it only exists as a very affective and interactive structure of feeling about the war and the state that Russian people have. Maybe the best exploration of it is only possible by reading across various chapters of the book. And reading out from Lisa Wadeen’s work on how, to paraphrase here, the simulacrum of charismatic authority tends towards shabbiness, decay and deformation in such regimes. It produces anxiety as much as compliance.

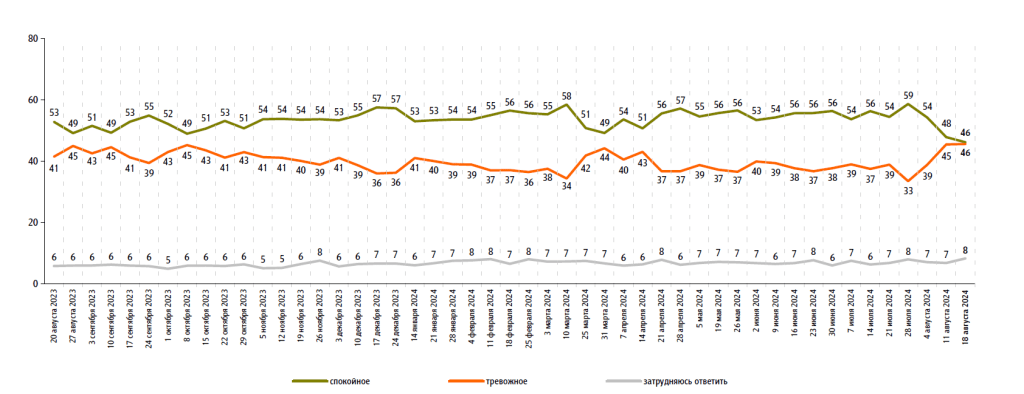

Finally, I wrote way too many posts about the problems of relying on survey data showing high war approval among the Russian public (a public which of course does not exist and knows as individuals that it cannot have an opinion). One of my most viewed posts in the last four years is this one about the shabby and unprofessional reality behind the smooth veneer that is the curation and presentation of much survey data about Russian political opinion. But don’t believe me, check out this pretty devastating indictment of interview practices which shows how the majority of answers to questions involve information loss, misunderstanding and distortion.

The title of that article is ‘communication breaches’ and for me this continues to be the lesson of the war when it comes to its impact on scholarly discussion and public understanding. Will this change before the war ends? I doubt it, meaning that publics and politicians are also not ready for the new European reality the end will bring – in terms of the new kind of Ukrainian and Russian regimes and states which will emerge and the necessity to have some kind of plan to engage with both. Will they be ‘the same, yet worse’ as I predicted in January 2022?