What are the sources of social coherence and stability in Russia, three-years and six months into the invasion of Ukraine? This is the first of three posts (I hope) where I outline a theory of ‘soft authoritarian administration’: the ubiquitous intrusion into everyday life of securitized administration but which is not experienced (mainly) as coercive because the main vibe is the comfort and convenience it increasingly appears to provide to the majority of Russians. But this first post is preambular. I just finished reading the new book on elite ideology in Russia and I recommend it. However, at the same time, it for me, illustrates a lot that’s wrong with expert and academic commentary on what makes today’s Russian state ‘legitimate’ to many.

Despite many dissenting voices, too much attention is still afforded to the putative strength of a wartime ideological consolidation. And this is partly the fault of non-Russia specialists fighting Ukraine’s corner, for good reason. They need to paint a picture of brainwashing and and national accord in Russia to mobilize support for their cause. Less charitably, this position steers close to simple outrage framing for clout.

By contrast, there are professional observers steeped in political philosophy such as Marlene Laruelle in her new book: an extensive history of, and conceptual guide to the ideas she sees as formative in Putin’s Russia. Ideas about a counter-hegemonic civilization that translate into a broad societal compact between elite and people. In my view, Laruelle, because she’s too good a scholar to give in to simplistic narratives, ends up somewhat undercutting her own thesis: civilizational tenets are a ‘repertoire’ of semantic elasticity and gaps, more ‘scripts’ than programmes or world views. If readers want, I can do a full post reviewing the book, because it’s well worth a read.

Serious works like Laruelle’s aside, it’s hard not to be incredulous when I read how much headspace ideology takes up among Western scholars. In a sense this is ironic because ‘we’ in the West treat it in many ways much more seriously than Russian regime intellectuals themselves. This approach has some serious limitations when it comes to doing adequate political sociology. Often a ‘values’ approach is not so far from the extreme positions of those like Timothy Snyder who propose – usually to the surprise of social scientists – that Russia is a more or less fascist state.

The research agendas based on tracing how ideas influence populations are always attractive to scholars and activists alike because they’re simple to grasp. But they’re a poor substitute for sociology, and they too often reflect an outmoded view of how ideas circulate. Not only that, they are invariably a reflection of deep conservative pessimism among their practitioners. Essentially, they propose that most people are more receptive to negativity than a positive agenda.

‘We are for normalcy, the Europeans are not’, is the kind of negative conservative agenda I am talking about. This is hardly attractive when Russia remains a country of whopping corruption, precipitous demographic decline, terrible infrastructure like run-down schools and hospitals, not to mention extraordinary low salaries by global ‘middle-income’ standards and horrible labour relations. Europe has indeed become a useful distraction in discourse; an external, threatening other of moral relativism, sexual deviance, racial disorder and political deadlock in media and state discourse. ‘Things might be bad, but at least we’re not in France’, is a sincere, if unintentionally humorous phrase one might hear as a reflection in everyday talk of elite narratives. So, some of these ideological conjuring tricks gain traction then, especially as they are finessed into a biopolitical defence against moral decay. But if the regime is so bent on defence of tradition and the Russian people, why are social blights still rampant, and prenatal and profamily policies so mean and tokenistic? While there is support for neo-conservative ideas because of general fears and the legacy of the 1990s, there remain many concerns that far outweigh the propagandized issues on TV: inflation, impoverishment, fear of unemployment, economic crisis, and indeed, fear of armed conflict. Just in the latest Academy of Sciences Sociology Centre polling, these fears, over remain very high on the agenda.

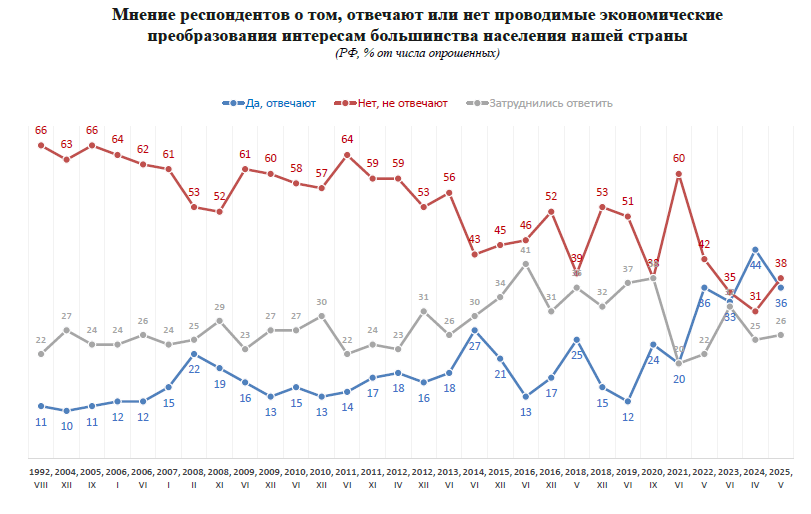

Dashed expectations that the war might be changing the social compact in favour of better pay and conditions for the majority explains the most interesting May 2025 findings from the Russian Academy of Sciences Sociological Centre: a big rise, and then fall in the numbers of people saying that economic transformations have been carried out (when? The poll doesn’t specify) in the interests of the majority. This measure was notoriously low until the war began. Consistently, less than a quarter of respondents would ever answer in the affirmative. On the eve of the war, the number of people correspondingly agreeing that Russia’s political economic transformations served only the elite was the highest since 2011, at 60%.

However, since 2022, this indicator in particular has been extremely volatile. In 2023, for the first time ever, the indicators crossed over into a scissor formation – more people – 44% – agreed for the first time that the economy was being run for the benefit of the majority. However, things have ‘scissored’ again back to a position where the majority disagree that the economic regime serves their interests in 2025. This volatility is unprecedented and indicates deep-seated political frustrations that few other quantitative indicators can uncover. The economic consequence of war were – perversely – expected to provide not only relief from the neoliberal compact, but more than trickle-down prosperity – as production was to be reshored and incomes raised.

The burgeoning disappointment that there is no ‘war dividend’ let alone the prospects of a peace one, help us uncover the peculiarities of the actual politics of Putinism – the flip side of soft repression is one of providing ‘comfort’ and respite from harsh economic reality. And I’ll cover the ‘comfort-class’ soft authoritarian administration of Russia in the next post. For the time being, I have a little challenge to readers interested in Russian media: try counting the instances of ‘comfort’ in the coverage you encounter. Ekaterina Shulman interestingly refers to the discomfort (in multiple meanings) of losing access to YouTube for Russians in her latest interview. She examines the loss of YouTube in the context of what she sees as the ‘destruction of the fabric of everyday life’ [bytovaia zhizn] which in Russia provided a high level of comfort to the metro middle-classes unparalleled in Europe (in her view from Berlin). And it’s very present too in this tone-deaf piece on emigration by Kholod media, in which comfort and convenience, more than intercultural adaptation or integration are emphasized. [sidenote: there are plenty of French supermarkets in Buenos Aires and better choice of quality low-cost clothing stores than H&M]

Bytovaia zhizn – everyday life – as Russian Studies students should know – is a hard phrase to translate into English because of the connotations it carries, not least of which is the idea that the creature comforts of retreating into a private domestic life can ward off the scary reality beyond one’s front door. As Catriona Kelly wrote, in 2004, in a chapter on byt, ideologists of all stripes in Russia have always had a problem with byt. But what if material well-being itself as a direct result of authoritarianism could become a kinds of ideology? That question will be covered in a future post.

Would love to see you review Laruelle’s new book.

LikeLike

Pingback: Is ‘Putinism’ a coherent ideology? Do Russians identify with it? | Postsocialism

Pingback: My 2025 roundup – The old world is dying; now is the time of monster posts | Postsocialism