I was asked today to answer this question by a journalist, so I thought I’d share my responses. Thanks to Jesper Hasseriis Gormsen for asking it. And check out his [Danish language] podcasts on Russia http://intetnytfravestfronten.dk/

This is a really tricky question, but what I want to stress is two things – like many other polls, the answer might not be telling us what we think it is. The answer might be to a different buried question in the mind of the answerer. That question (among others) might really be ‘why do so many people live so badly now, when in the USSR they did not (or at least everyone was in the same boat, more or less)?’ Thus eliciting the answer: ‘Yes, I do regret the collapse of the USSR.’

Note (and I guess it needs saying), that this is not my opinion of what the USSR was like (as if there can be a single ‘reality’ of lived experience of an incredibly diverse state that existed for 70 years), just an interpretation that might well be ‘real’ to the person who is asked the question.

The second thing is that poll answers are overly and frustratingly simplistic answers that actually express (or, as I have just said, obscure) very complex feelings and values of the people they are asked of. It is amazing that when I talk to political scientists, they often don’t really believe this in their heart of hearts. Take for instance Brexit or Trump. These ‘answers’ are not merely, or even mainly, about ‘immigration’ or ‘racism’.

Thirdly, the devil is in the detail of the question. It’s well known that survey questions can be phrased and ‘hacked’ to significantly change the result – and pollsters know this (or should do). I don’t think that’s the case here. However, Levada, by using the term ‘collapse’ [raspad] does set out a particular ‘framing’ inadvertently, of the ‘ending’ of the state called the USSR in 1991. One that sets up in the mind of the person answering it, even if they are too young to experience it themselves, the trauma of postcommunist transition. Here we might add – why wouldn’t someone sensitive to the past, or lacking clear ideological support for ‘actually-existing capitalism’ answer: ‘Yes, I do “regret” the passing of the USSR, the state I was born in, or that my suffering parents were born in and worked hard all their lives for.’

Let’s turn the phrasing around. If Levada asked: ‘Do you regret the founding of the Russian Federation in 1991?’ I’m pretty sure the majority would say ‘no’ and so the poll would in a way be reversed.

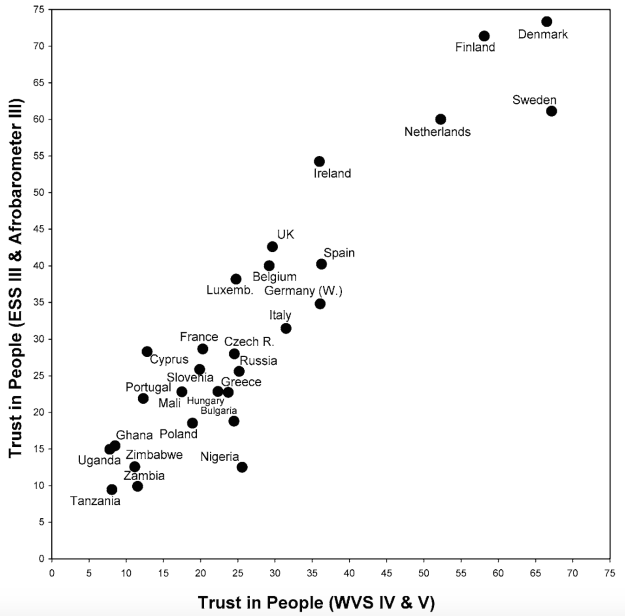

Here’s the poll in question.

https://www.levada.ru/2018/12/19/nostalgiya-po-sssr-2/

Note the fluctuation since 1999 of around 20 % of the ‘regret’ vote (however, most ‘regrets’ are in a band between 53% and 65% since 2005). (Don’t look at the graph, look at the table). This fluctuation could be to do with people with direct experience of the USSR (positive or negative) dying along with people with no personal experience thinking in more rosy terms about the period – hence a kind of up and down wave effect. But, you would also expect nostalgia to rise according to periods of crisis. When people feel their lives are not going to plan they might well look back to a ‘simpler’, more ‘stable’ time with nostalgia. That’s plausible for the figures in 1999, 2000, and 2001 when people took a massive cut in living standards due to the Defolt. However, that is not borne out by the data here when taken in terms of trends over time since then. So perhaps there is not clear answer as to ‘why’ the numbers fluctuate. Here we could have an aside about polling most often telling us ‘nothing’ directly related to the question.

Now to the question of the meaning of nostalgia.

In her wide-ranging book The Future of Nostalgia, the wonderful Svetlana Boym identifies two distinct types of nostalgia: ‘restorative’ nostalgia and ‘reflective’ nostalgia. Restorative nostalgia, “puts emphasis on nostos (returning home) and proposes to rebuild the lost home and patch up the memory gaps.” Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, “dwells in algia(aching), in longing and loss, the imperfect process of remembrance.”

Boym was first and foremost a Russian cultural scientist with a deep commitment to the personal insights lived experience provides for research. We can ‘read through’ her descriptions to suppose that both forms could be operative for nostalgia towards the Soviet Union. And as their psychology origins suggest, nostalgias can be personal quirks, irrationally warm ‘affective’ feelings, passing infatuations, or indeed pathologies bordering on madness. I suggest that all these are operative in different people at different times in the last three decades.

Lastly, we can break down nostalgia into a scale of more ‘rational’ interpretations by people. I rank these not in order of importance, but in terms of macro-to-micro social scale. All, some or one may be simultaneously operative in a person’s mind when they answer the pollster’s phone call – in fact none of them might be operative and the person getting the call might just want to get the pollster off the line!

- Nostalgia for Great Power status (empire and the respect for the geopolitical might of the USSR). See Mazur below (and Kustarev) on the ‘myth of achievement’ and the ‘myth of power’.

- Political order (totalitarian as a system that ensures a lack of political and civil strife, that obviates the need for the citizen to perform any political roll – relief at this and thankfulness – particularly effective in those that see the 1990s as ‘chaos’). See for example, ‘We grew up in a normal time’ – the title of a chapter in a book by Don Raleigh on Soviet baby boomers.

- Social order (“to each according to his needs”) – the Soviet social contract (which Linda Cook shows was failing in large part by the 1980s). Related to this, as in the West, a period of sustained social mobility. See, for example, Liudmila Mazur’s ‘Golden age mythology and the nostalgia of catastrophes in post-Soviet Russia’, although her polling data paints a more complicated picture of the ‘myth of prosperity’.

- An emphasis on the sincerity in personal relations, the intensity of personal trust and reciprocity given the ‘heartless system’ of the USSR – note how this is contradictory to point 3, yet perfectly possible to hold this belief at the same time as number 3. People are like that.

- Nostalgia for the time of one’s youth (probably universal – hey, I think the early 1980s in the UK were great, but ask a miner or other person from the North that). Nostalgia for personal and more widespread idealism (the BAM-romanticism factor) that accompanied this. See Mazur on the ‘myth of achievement’.

- Recognition of Labour(due recognition given to labour as the primary factor of production). Not that I am not saying that work was more ‘dignified’ or better paid than in the West during the Fordist period after WWII. Merely, and this is what most of my research interrogates, many working-class people feel nostalgia for what they perceive as a better time before the present. They highlight particularly, relative lower inequality (everyone was paid badly!), relative degrees of social compensation for labour (the social wage and labour paternalism included subsidised childcare, faster routes to social housing for workers, subsidised food), the team-level autonomy of work given the dysfunctional industrial system – bottle-necks, old equipment, distant management, shortages – all these led to a large degree of control over work, as enterprises looked to individuals and teams to find quick and dirty hacks to solve these otherwise intractable structural problems with the Soviet economy. Another way of looking at this is to say that workers had little or no political or associational power in the USSR, but they did have structural (work-place bargaining, or ‘contingent’ power).

Also operative are the answers that regret ‘loss of homeland’, ‘destruction of kinship and other ties’ – these are offered as options in the more detailed poll question. However, I think my 6 are more heuristically persuasive than the dry promptings of Levada, including the most important one: ‘the destruction of a united economic system’, although my points 2, 3, and 6 could be version of that.

Note that nowhere do I find it persuasive that there is nostalgia for the overly abstract notion of ‘communism’ as a system or the ‘communists’ as a ruling party… I intended to reference this piece on the mythology of the Soviet Past by Kustarev, but didn’t have time in the end. I highly recommend it. Александр Кустарев, Мифология советского прошлого «Неприкосновенный запас» 2013, №3(89)