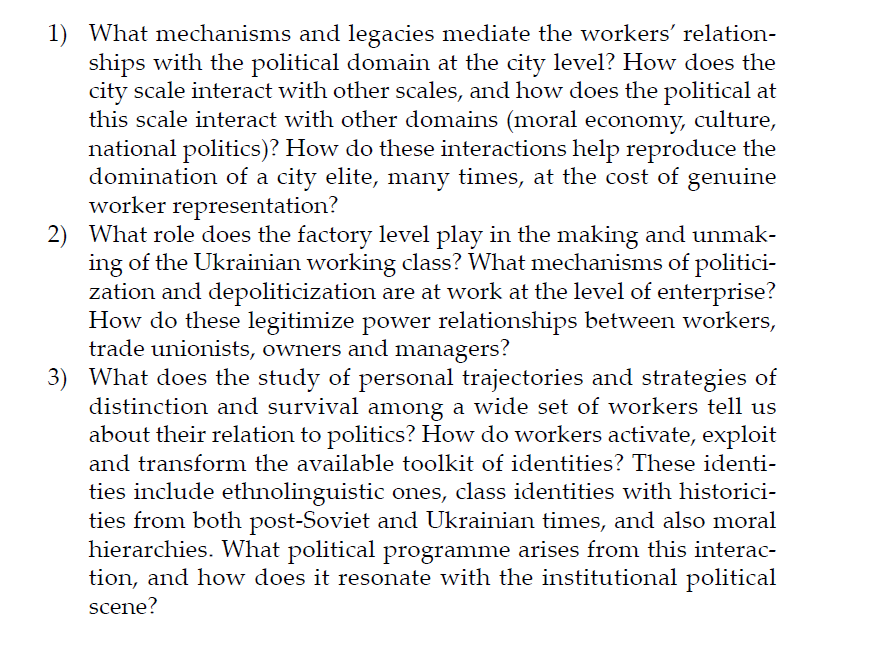

In the last post I mentioned….polsci. I don’t talk about much contemporary political or sociological theory in the book, but I am interested in a moment from early 2000s where Douglas McAdam and his co-authors Tarrow and Tilly appear to countenance a ‘poststructuralist’ way of looking at social movements

Following Tilly et al, I pick up on the call from more than 20 years ago by these authors to better integrate cognitive, relational and environmental factors pertaining to the submerged reality of political movements and networks. To reiterate – we’re looking at sums of effects of the flattened public sphere by criminalizing protest, the beheading of movements’ charismatic leaders. This, I argue, forced on activists a more democratic and grassroots focus; Putin’s 2020s Russia produces a new and in some respects dynamic activism, as much as activists’ ideological commitment or material resources do. This is the conundrum of social movement studies – the gap between foundations of action and action itself – how does a ‘process’ of activism occur or not occur in the presence of network and commitment? Again, this is something I started exploring in a direct response to Tilly’s work in my previous co-edited book. In this new book, I look more broadly at how much in common anti-war activism has with labour organizing, ecology work, and even grassroots patriotic activism in support of Russian soldiers. What I find are related processes of dispersed, nomadic activism. But there is a long gestation and formation of political positions that then informs action. Once again, that is the value of a ‘submerged organizational level of analysis’ (Tilly) – and one I aim to provide.

I follow a detailed process-tracing of anti-war stickering in 2022 in the case of ‘Polina’ in my book. To do something like this, most researchers need to start with the formative experience of 2011-12 around Bolotnaia, but also acknowledge the ambivalence of that experience. It has an affective hardening effect against Putinism, but also set up tensions around the question of electoral v. other politics, committees v. charismatic leaders, the centre v. periphery, talk v. action. It would be culturally reductive to say Bolotnaia radicalizes, or sets in motion a series of learning points in a predictable way that results in where we are now. Just to take the composite characters again from my book: ‘Polina’ becomes attuned to a genre of public protest opposition despite Bolotnaia’s failure, and despite the inflation in repression after 2018. Indeed, she goes against the advice of her allies among Navalny organizers when she stages a spectacular protest with others about Shiyes and gets her second arrest. At the same time, the stratum she ‘represents’ learns a lot from Navalny’s electoral strategy and how it involved regional capacity building: essentially, political education in organizing. But this for Polina occurs in parallel with her learning from socialist labour union work that’s mainly ‘indigenous’ to her locale.

But contrary to what you might expect, this is not taking place slowly, or gradually because it is occurring at the same time as an explosion of private (not public) social networking capacity. This means temporary alliances are possible between regional Navalnyites and ecologists and labour/socialist organizers. And these alliances are horizontal and nothing to do with the actual leaders of the Navalny movement. Indeed, it was funny when I interviewed a prominent person formerly connected to FBK and they had no idea of the capacity they had really built regionally because it was invisible to their own, centre-focussed and civic-electoral political aims.

In a sense, this process is frustratingly fuzzy to the social scientist; it remains very contingent, situational, refutes to a degree simplistic findings about the driving forces of identity politics or rights-based discourses for the emergence of social movements. In that sense, my argument is not novel. Activism is opportunistic and, indeed, in a marginalized positioning. At the same time, the relative field of possible causes/actions/political orientations with which to align or ally expands in a noticeable ecumenical and pluralist manner – even to a degree which people are uncomfortable with in reality – like in joining members of the (regional) Communist Party in actions despite their prior mistrust and continuing unhappiness with the leadership of that party. As a result, there’s certainly merit in thinking about activism in Russia as an example of dispersed, pluralistic, and flexible political contestation.

But there’s also merit in thinking about how to put the ‘social’ back into the idea of social movements. Alain Touraine in the early 1990s remarked that post-social movements were heralded by consumerism and individualism and the abandonment of grand political aims based on class-consciousness. Movements base on identities threatened to pacify ‘social’ claims like a greater share of national wealth. But now we can think of the socialness of activism in a different way. What was interesting to me is how the actual differences and relations in communities of action are naturally visible and reflected upon by participants. And this carries over into relations between activists – so it was telling that while Polina didn’t like Navalny’s politics (too metroliberal and cryptonationalist) – she recognized the importance of her relation to the former Navalny organisers. At the same time, she didn’t like the anticapitalist socialist position of some unionists, but admired their actionist stance and picketing tactics. So, in a sense what I’m arguing for here is that the ‘social’ after the virtualization of opposition remains an important part of political engagement. The social as solidary and mutual learning still serves as glue and trumps political differences. Of course, the extreme turn of Putinism only helps this.

However, it’s also not that simple as having a common enemy. The war has forced people to confront the necessity of engaging with, or just listening to, those who support minimizing the damage to the Russian Federation while still broadly opposing Putinism. And in the last part of the book, I show this drama play out. Died-in-the-wool anti-war people are forced to acknowledge the legitimacy of activists who want to protect Russian soldiers even while those don’t support the actual war aims. Just a few days ago there was the case of a prominent anti-Putin socialist activist who was killed fighting in Ukraine. Oppositional activism is really only a small part of the book, but the tectonic social impulse that allows me to legitimately compare anti-war and patriotic activists is a recurring theme that provides the master theory underpinning all my ethnography. I turn to that in the following post.

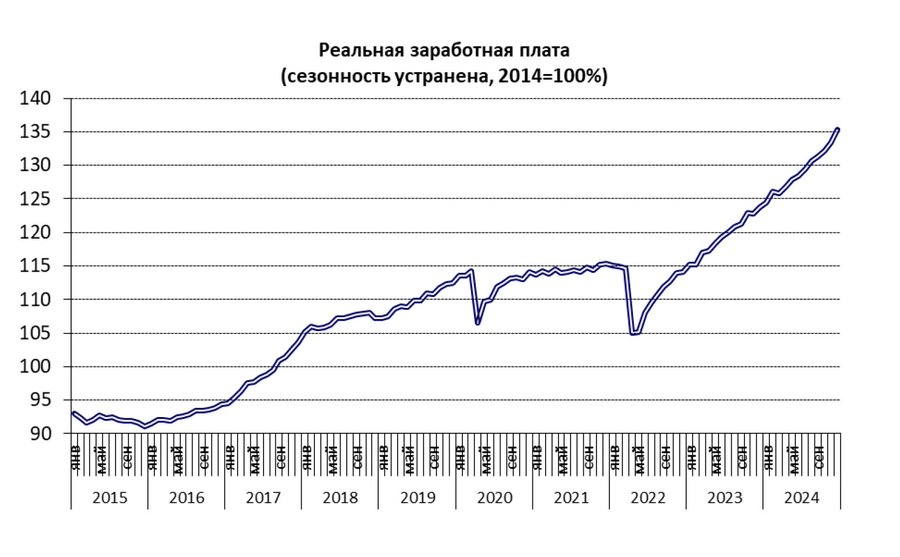

Coda: What’s in the news? I read this article today about how only 10% of men in Russia admitted that they would feel awkward if a woman earned more than them. A linked article notes that the general gender pay gap in Russia is 43% (average salary for men 1000 USD and for women 720 USD). In turn this reminded me of a chart that Maria Snegovaya and Janis Kluge posted on social media showing a strong uptick in ‘real wages’ since the war began. Snegovaya sees this as support for the idea that the ‘population is loyal’. Kluge wrote that it shows why the war has been a ‘golden era’ for many. People assume that when I criticize these stats I am saying that they are ‘faked’. I’m not saying that, though I do think out of desperation at the poor quality of data they get that people in Rosstat have to process it a lot and that this alone is ‘dodgy’ – but something all statistical agencies do. What I’m really saying is: how reliable are the sources of this data in the first place when we know that what people actually get paid in Russia is one of the most notoriously opaque and painful data points in any statistics.

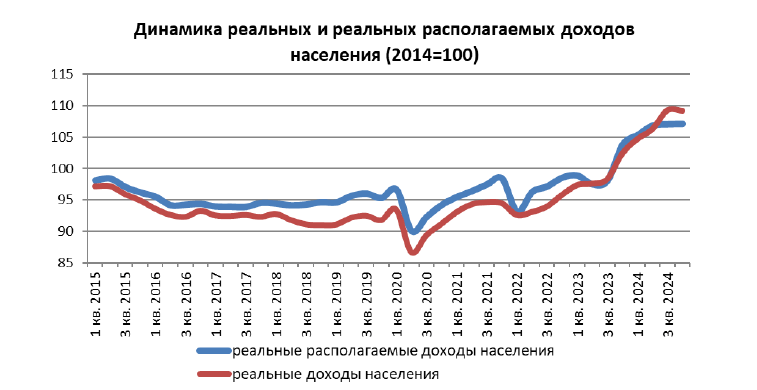

Anyway, to illustrate how silly it is to rely on one dataset like this (which in the original has no explanation of source), I just posted another graph from the same source. This is ‘real incomes’ (red line) and real disposable incomes (blue line). Details aside of the difference between incomes and wages, what’s perhaps most remarkable is the incredible stagnation of incomes between 2014 and 2023.

Axes of evil, or just normal chart crimes? The discussion in Russian to M. Snegovaya’s post is interesting. As is a follow-up post by Nikolai Kul’baka. He gives details on how wage data is collected from firms. As one can surmise, such data is not collected from small and most medium businesses. State enterprises we know do not reliably report salaries. A few v. high salaries distorts the average. The methods of calculation have changed a lot. Kul’baka: ‘there’s no major rise in salaries in Russia’. He also notes that protest frequency and changes in wages have no statistical correlation, something Sam Greene and Graeme Robertson explored many years ago in this excellent article.