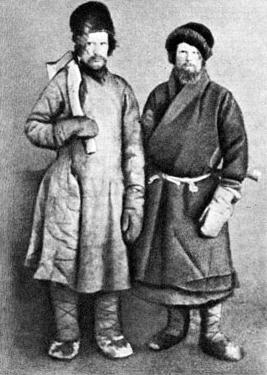

Because we’re talking endlessly about the inability of many Russians to admit they live in an aggressor, neoimperial state, or even register the reality of what’s happening, I thought I’d go back to this piece I wrote about doing fieldwork in 2014 and after.

I went back to the field after Maidan and Crimea, but just before the 2014 Malaysian airliner MH17 downing during the war in Donbas. I wanted to write about the sensitivities of doing fieldwork in such times where I was already seen as a representative of an enemy country. The shoot-down event is on my mind because of 2022 Ukrainian allegations that Russia is planning a false flag operation to shoot down an airliner over its own territory using Western weapons transferred to Ukraine.

Unfortunately, as with a lot of academic projects that are spun out of material for different purposes, the article is a bit of a mess. Too many themes and ideas. Boiling it down in this post, here are some of the ideas which still have relevance.

‘Political’ events are not experienced the same way and post-truth media makes things worse

I opened my news feed the day the airliner was shot down and experienced shock, disbelief and nausea. Pretty soon it became clear that Russian forces in Donbas were responsible. However, what was for me the defining ‘event’ was no such thing for 90% of Russian people. Firstly, there’s a tendency to delay and obfuscate big news like this – remember the flat denial and then spinning of the Moscow Cruiser sinking just recently. This seems ridiculous to people paying attention in the West, but it ignores that it buys time for the second stage: the post-truth coverage by Russian mainstream media. There are seemingly smart people who believe the corpses of the victims from the airliner were transported to Ukraine. This is not so different from 9/11 truthers. But this is in a society where media allows such post-truth versions space to breathe and spread. Having said that, at the time there were people who saw this event as THE dividing line. A crime so terrible that there would be no coming back for Russia. This was also communicated to me in the field. After this event some people already made plans to leave Russia, or even prepare for nuclear war.

People internalize propaganda as a structure of feeling even while avoiding ‘news’

That day I went to a birthday party held by some friends of mine who are well-to do in the cultural scene. They’re average, upstanding Russian middle-class – politically loyal people. Stupidly, I expected the ‘event’ to overshadow our party; most people were not aware of what had happened. Later I observed ‘avoidance’ as the most common response to what was going on in Donbas. While the television blares continuously in the background and clearly shapes how many people respond to the war on Ukraine, this effect is much more indirect and insidious than people generally think – it’s a vaguely felt itch at the back of peoples lives through their interaction with television as a form of verbal and visual wallpaper. While I don’t think direct comparisons to Nazi Germany really work in general, the ‘Ukraine question’ is a little like the ‘Jewish question’. Over a pretty long period of time, constant and building anti-Semitism in public life created a strong social desirability bias of hatred and blame towards Jews. Once war came, this in turn allowed enough fear, resignation and – mainly – indifference to be produced so that the Final Solution was possible by that small group of willing executioners and a much larger group of loyal bureaucrats – Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. Many ordinary Germans were also guilty of latent anti-Semitism which the regime successfully leveraged. The point is the mass of people for whom even after 2014, Donbas was a low-salience issue and so they easily fall in to the ‘structure of feeling’ that the regime helps foster: “Ukraine = bad, West manipulates and betrays, We are the victims, We won the war. We are righteous.” Just a few weeks ago, I mentioned the Malaysian airliner to a Russian who is deeply ashamed of the invasion and politically aware. They’d completely ‘forgotten’ it!

Silences and pauses can draw attention to the discomfort with political events

So my article is really about trying to interpret pauses and silences where people don’t acknowledge or mention the elephants in the room. I argue that forms of silence and acknowledgement of the other person through silences – uncomfortable pauses – are themselves forms of communication about ‘political events’. This is heightened when one of the people is a Russian and the other is a foreign person from a Western bloc state. I conclude the first section: “Interlocutors and researcher are forced to negotiate the event within their everyday encounters in a way that maintains civility and the possibility of an ongoing commitment to relations. This is the ‘intimate’ reconstruction of (geo)political subjectivities.”

Victim narratives go far back and scaffold the current shared ‘feelings’ in Russia

Some of the rest of the article is about how clearly, even in 2014, Russians articulated a victim narrative and how effectively Putin has manipulated this. (I came across this excellent post by Anna Razumnaya on victimhood stemming from feelings of inferiority and humiliation). This framing goes back to the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 where I first experienced the deep-seated sense of geopolitically ‘structured feeling’: outrage and resentment that was sincerely expressed, but mainly communicated through emotional reactions – like my colleagues demanding of me a ‘political statement’, and then walking out of our shared office in Moscow, or the ‘dirty’ protests where people smeared the US embassy with faeces. The conclusion here is that ‘willingly or unwillingly, we come to embody public diplomacy’ in some way in fieldwork under such circumstances. Is it possible to overcome the way we are unwillingly inserted into this position?

To confront or to maintain tactical silence?

Sometimes we have time and space to talk about geopolitics in a considered, intimate way with people who have different worldviews, but mostly not. We could argue that it is important to signal strong disapproval of the invasion and support for Ukraine. I think that’s true and essential for Russians talking to Russians. But for ‘non-native’ researchers, confronting people politically is completely at odds with anthropological practice in fieldwork. But it is sometimes interlocutors who confront the researcher. What is she to do? Confront back? Unfortunately, this is part of the geopolitical script the Russian media have anticipated. More often people laugh at you: ‘You’ve been brainwashed by Western media.’ Adopt the ‘silent’ approach of many Russians themselves? Can ‘tactical silence’ express more? Can just the persistent presence of the representative of the other have jarring political effects? Scholar Yael Navaro talks about silent, phantom presences ‘irritating’ people even as they try to carry on as if nothing is happening.

Silence can invoke opposition and resistance, but it can also signal indifference and consent to barbarism. That’s why it’s important for Russians who oppose the war to carry on making small symbolic acts of resistance. As one activist said to me recently: ‘all I’ve got now are these anti-war stickers, but they mean so much to me.’

The visible resistance to war might allow a change of tactic: from being silent ourselves to forcing the silences and pauses on to those who say they support the war. Make them think, and make them confront the idiocy of the argument Razumnaya highlights: ‘We’re bombing Kharkov so that the West would fear us’