This post was earlier published on Riddle: https://ridl.io/divergent-economic-experiences-of-war-the-rich-get-richer-and-the-rest-don-t/

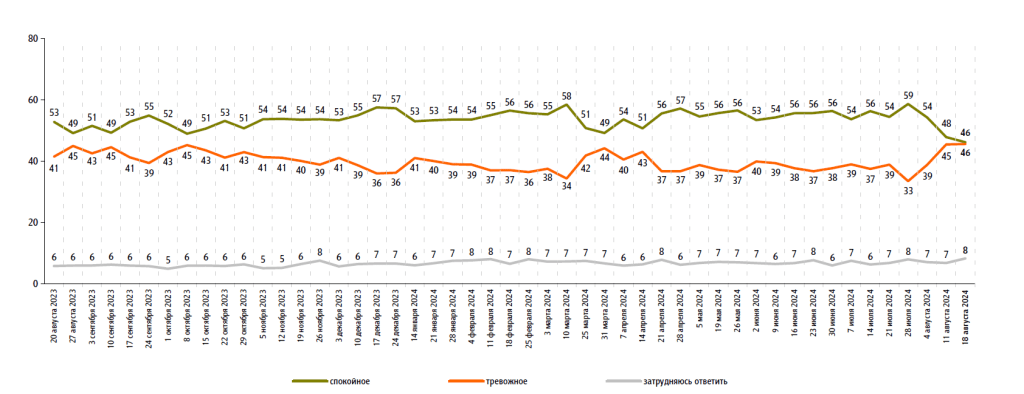

Discussion of the inflationary side effects of war spending in the Russian economy has been inconsistent. Even when observers note how in the long term economic decisions store up trouble, many focus on a mistaken idea that a significant segment of Russians are feeling economic benefits, or that wartime spending means real gains (as a share of GDP) for labour (i.e. that gains are redistributive).

Now it’s true that the government did signal a willingness to depart from decades of austerity when it comes to funding the war, but as Nick Trickett points out, spending more to foster growth only works if productive capacity actually expands as a result. Historically, fiscal expansion has increased demands for imports instead of domestic output. Despite recent rises in GDP, a rebound from the economic shock of the start of the war and indeed, the long recent history of Russian underconsumption and underproduction continues.

In the piece from August 2023, and in a recent follow-up piece Trickett offered a corrective to the idea that wages have seen a sustained outpacing of inflation. Incomes are still probably lower in real terms than ten years ago, even accounting for a 9% rise in 2024 (these are the latest Rosstat figures. In 2022 real wages fell by 7% according to RLMS; in 2023 they rose slightly). In other words, Russia would need a decade-long shift in the share of income accruing to labour, and a similar period of real income (over inflation) increases to register. And the actual trend since 2017 is downwards.

The norm of low wages means that big percentage increases matter little to people

This point about the longer-term context is echoed by another granularly serious observer, economic geographer Natalia Zubarevich, who in every interview emphasizes the ‘law of small numbers’. Even a 20-40% rise in your take-home pay (which might well be experienced in well-placed blue-collar jobs over the period 2022-2024), does not mean very much if you’ve been working for subsistence wages for the last decade and set against high ‘real’ inflation.

Eurasianet discussed the manipulation of official inflation statistics in 2023, citing alternative sources which estimated real inflation at 20%. One of my better-off informants was called in to Sberbank for an interview in November. Her high level of rouble deposits was a concern for the bank worker who recommended she reinvest in gold and that the internal calculation by the bank, shared with high net-worth customers, of real inflation was 43% in 2024.

Widespread pessimism and dissatisfaction among wage earners, contrasting with optimism from business owners is what I find in my latest round of interlocutor interviews. These are taken from the same set of research participants I’ve been engaging with since 2009 in a well-placed part of Kaluga region – itself a ‘goldilocks’ zone of development near Moscow. Added to the mainly working-class men and women in my sample, I’ve extended my reach to new entrepreneurs who have expanded business since 2022, as well as more middle-class interviewees in Moscow and other large cities. Here, I condense around 20 hours of talks since early November 2024. For readability and ethical reasons, these are composited characters.

The view from the Kaluga-Moscow corridor

Gennady the small-business entrepreneur is ebullient. Patriotism and making money go hand in hand for him. The exit of Western companies allowed him to lever a wedge, going from importing and selling catering equipment via a US-based supplier to now dealing directly with the Chinese manufacturer. Gena is proud of his ability not only to markedly increase his profit margin this way, he has ‘onshored’ a small, but significant part of the production process involved. He now employs three times as many people as before and a third of those are in primary production – making components that are disposable parts for the Chinese equipment. Russians are like “sponges” when given the right opportunities to learn. They’re also like “mushrooms” – given the right conditions, they thrive and grow.

Gena likes his organic metaphors, but most of his talk is full of anglicisms taken from corporate speak. When we were chatting in Russian it took me a while to work out that when he was speaking about ‘khantil’ for able workers, he was using the Russified past-tense form of ‘hunt’: ‘I’ve been on the hunt for a good freight driver’.

At the same time, Gena says that reacting with resilience and entrepreneurialism is not about ‘patriotism’, but about the need to get ahead and make money. Nonetheless he makes it a point of patriotic principle to end our talk by saying ‘As you are recording this, let me say that we will win the war. Victory is ours’.

Misha is a technician in an industry that should have benefitted from spill-over of orders from the military industrial complex. I can’t be more specific than that, but I’ve never seen him so negative – and he is one of the classic ‘defensive consolidators’ who shifted from opposition to the war in 2022 to acceptance in 2024. Misha’s enterprise is affected by the shortage of workers. Because there aren’t enough workmen, he is not getting enough hours as a technician as not all the equipment can be utilized. The shortage of workers is not because of the war – few people in this region have volunteered for the front. The bigger picture is the one I highlighted at the outset – even with a wage increase of 60% since 2022, for many, the job is not attractive enough in comparison to lower-skill/stress/pace work in Moscow or elsewhere.

There’s also the major demographic squeeze in general – the c.1% annual fall in working people available nationally. Misha talks to me a lot at the moment because even when his plant is up and running, his boss has to meet his demands for more flexible working hours, so sensitive is he to losing more workers. His micro-situation is a good illustration of broader processes – like the ‘work to rule’ in the Moscow metro because of a shortage of staff there but the inability to improve pay and conditions. This implies something of a negative feedback loop for productivity. The more an employer ‘sweats’ assets, be they labour or capital, the sooner they meet hard limits on increasing output, and even reversals.

Misha’s working biography features prominently in my new book, illustrating the ongoing sense of economic insecurity even for people like him who have good social, economic and other ‘capitals’ (he has a higher technical education in a good sector). I’ll merely highlight Russia’s “labour paradox” – workers can sense their structurally strengthening position – via falling demographics and specific labour shortages, while at the same time as suffering from the overall marginalized power in bargaining. In Russia, one can bargain only with one’s feet. This paradox, viewed in aggregate, suggests that workers may be able to demand more where they are in industries serving state demand, yet eventually as the overall position deteriorates further, their bargaining power may prove transient. Whether or not some kind of authoritarian corporatism is possible (where there are real concessions to labour led by political recognition of its need) remains to be seen.

Misha is as well-educated and ‘worldly’ as Gena. He is insistent that the ‘situation’ of workers has only deteriorated, even as he makes a careful distinction in terms of class (that he’s not a worker). He’s been monitoring the job boards because at the beginning of the war he was looking to move into a job that would protect him from mobilization – perhaps metallurgy (another informant successfully made such a shift). Downshifting of work, after all, is a political strategy that goes back to Soviet times.

Misha points out that drawing conclusions based on published wages is foolish. Nowadays you’d have to look even more carefully at the hidden conditions attached to the discretionary element of the wage. Like others in my sample, he has left jobs where the published wage was higher but it required much greater self-exploitation at work. He even gives an example of a forklifter in a cement plant. Your ‘norm’ might now be 50 tonnes a shift rather than 25 tonnes, while your pay has only gone up by 25% since the beginning of the war. Working much harder not only wears you out, it’s dangerous as the risk of accidents exponentially increases.

Then there’s the continuing significance of working-class male breadwinning in what is still a society where women are paid peanuts, even if they successfully undertake what Charlie Walker described as financial independence through leveraging service work positions. Misha’s wife is one such example and yet only earns half his wage, even though on paper her job (administrative) is actually more demanding in hours, skills, responsibility.

Misha, like most of my informants is incredulous as well as quite angry at the idea anyone could take seriously the idea that wages have outpaced inflation for anyone not a soldier or metropolitan executive. He’s not the only person to say: ‘100k’ (around $1000) a month for an average regional breadwinner’s job is the new ‘40k’. In other words, that 100 roubles only buys what 40 roubles bought a few years ago. And certainly, there are still many of his peers earning a lot less than 100,000 roubles a month in blue-collar jobs.

The official ‘subsistence’ minimum for a family of four is 70,000 roubles, leaving a paltry amount left over after basic food costs. And in any case, such measures are often based on absurdly manipulated calculations: like assuming someone can buy fresh fruit for 100 roubles a kilo in winter, or undercounting real heating and utility costs by around 50% because of the assumption that a person does not occupy more than an allotted 18 metres of living space.

Misha works. His wife works. They don’t have a mortgage but own outright a three-room apartment in a nice suburb. Misha has two cars (though he wants to sell one). He complains that real inflation is much higher than reported because even someone like him spends so much of his take-home income on staple food products. For the first time since 2009, Misha has bought 100kg of potatoes to store in his garage basement for the winter. Potatoes – the main source of carbohydrate for most since rice and pasta are often more expensive, have increased in price by over 100% in 2024 due to the poor European harvest. The ‘Russian salad’ basket of goods, is now around 40% more expensive than a year ago – and remember these are just the staples of poor people (carrots, cabbage, etc. )

Inflation in the ‘real basket’ of consumables is the dominant talk among everyone, even the wealthy Muscovites who shop in premium stores. One such informant points out that her favourite discount brand of wet wipes has tripled in price since 2022 and that this is a product made in Russia, not imported. Not only are there a panoply of online calculators for one’s personal inflation rate, people also read discussions in economic Telegram channels where more independent academic works on inflation and the cost of living are popularized.

Thus, one of my informants who lives on irregular freelance work and a disability pension pointed to the Russian household longitudinal monitoring survey (RLMS) published by the Higher School of Economics. He accessed its data via a Telegram channel. While the channel itself is sensationalist and firmly aimed at discrediting the Central Bank, the research from HSE is widely discussed by the channel members, including my interlocutor. Unlike official statistical services, the academic researchers are able to state things ‘as they are’, such as the fact that real incomes remain stagnant and indeed, have fallen in reality since the war thanks to tricks like lowering bonuses, not paying time off, etc. While RLMS confirms statistical facts like the long-term fall in poverty in Russia and even a fall in the GINI coefficient since 2022, the stark difference in measurements of real incomes stands out. RLMS records that average incomes are not higher overall than in 2013. Some of their calculations show real median incomes as less than half those recorded by Rosstat.

Tracking spending habits to calculate real inflation

Another way of looking at whether households are getting richer over time is to look at the proportion of incomes spent on different things. As people get better off they can be expected to spend much less of their income on staples and more on services and luxuries. Both Rosstat and RLMS look at this. The latter points to ongoing stagnation in services and non-perishable goods. Even today, Russians spend only 5% more on eating out than they did in 1994. By the same token, RLMS researchers point out that the sharp fall since 2020 of clothing spending is not due to a reduction in prices, but a sign of severe economic stress. Rosstat shows that households spend no greater proportion of income today on non-food purchases than in 2003. Even the richest 20% of households spend a whopping 26% of their income on food (in rich countries this figure is around 10%).

The main point of looking at the divergence in economic sentiment is to help understand whether war produces new social relations based on the relative shift in capital versus labour power. While people focus on real wage increases these need to be put in the context of the abnormally low wages in Russia, especially outside Moscow. We haven’t touched on household indebtedness and the cost of credit, the coming wage arrears crisis in multiple industries. Those are points to watch for. As mentioned earlier, for me of interest is the capacity (or not) of employers to turn to paternalistic reward as a way of dealing with the demographic-stagflationary crisis unfolding in Russia and which peace (at any price) will not solve.