I had been meaning to write a ‘roundup’ summer post, but didn’t get around to it. The Ukrainian push into a part of Russia’s Kursk region was obviously the most relevant event to write about, but even now there’s questionable value in trying to interpret. Here, though, I try to offer a number of quick summaries of events. And then some more speculative stuff. If you think this more topical genre worth reading, let me know.

Kursk is a kind of nowhere region in the Russian imagination (1943 tank battle not withstanding). It is not quite steppe country, not Cossack country, but neither is it core European territory either. Nikita Khrushchev was born here, but his formative years were in Donbas. Today, Kursk is a landscape of relatively successful black soil farming broken up by river ravines. I went on a road trip there in the late 2010s and one of my key interlocutors is going there next month for a family visit. When we visited together, despite the agricultural pride of the region, our hosts asked us to bring processed meats and cheeses (too expensive locally for poor people to afford), and essential medicines. The final leg from Kursk city took nearly as long as the one from Kaluga-Kursk along the highway.

In some ways Kursk’s dismal demographics and patchy economic geography are quite comparable to other regions – population depletion everywhere but the capital; agroholding expansion into spaces vacated by surplus populations; some economic specialization (iron and agri) despite not really having a competitive advantage; neglect from the centre and the pitiless poverty of rural life reminiscent of 19thC novels. Kursk is kind of representative in size too of many ‘central’ Russian regions. Kursk, Jutland (where I work), Maryland, and Belgium cover similar areas but compare populations. Jutland – 2.5m, Maryland – 6m, Belgium – 12m. Kursk, by comparison, is almost empty (well below 1 million inhabitants – and probably less given that population stats are inflated for budgetary reasons by the local authorities). Nearly 45% of the region lives in the single large city.

“What to say about Kursk?”

No, that’s actually the response my Russian interlocutors would likely say, if I was guileless enough to bulldoze them into talking about it. I did an experiment. I purposefully didn’t mention it to them for the whole of August (recall incursion began 6th August). By now, most people have had time to digest, but it still doesn’t have a political shape in Russian society. This is not because of propaganda, nor ‘indifference’. To some degree it illustrates the normalization of sequentialness of ‘externalities’ of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Invasion, routing of ‘our’ forces, war crimes, missile strikes on the mother of ‘Russian’ cities (Kyiv), counterattacks, drone strikes by Ukraine. Most ‘real’ is the indirect effect of inflation, loan terms and percentages, labour shortages, ‘opportunities’ for those able to relocate jobs. A handful of people reference Kursk. They’re not callous. They mention, wryly, the conspicuous absence of it on TV. They talk about helping displaced persons. They collect money and send it on. They bring collections of food, clothing and money to the temporary accommodation points (summer camps, ‘sanitorii’, disused student halls). Part of the story is one of the belatedness of meaning. It’s too early to say what the meaning of Kursk is on any level. We’ll incorporate it into the ‘meaning’ of 2024 probably long after New Year’s eve of this year.

“There aren’t enough men”; alarm versus calm

“There aren’t enough men”, was heard from that most loyal source. A ‘security-adjacent true believer’. Don’t ask me what that means, for now. Certainly ‘throughput’ or ‘flow’ of meat (because that’s what it is, and on the Ukraine side too) is inadequate. Something, somewhere will break. Or is right now breaking. Concerning a new mobilization wave I have many contradictory thoughts. On the mobility and ‘small tricksterness’ of post-socialist populations. On the tiredness of ordinary Ukrainians and Russians alike. Could mobilization just mean continuity? Yes, but continuity of what? Would it accelerate tectonic changes. Yes, that too. But that’s the point. We stand, as sociologists, reading a seismograph that’s too far from the epicentre to make predictions.

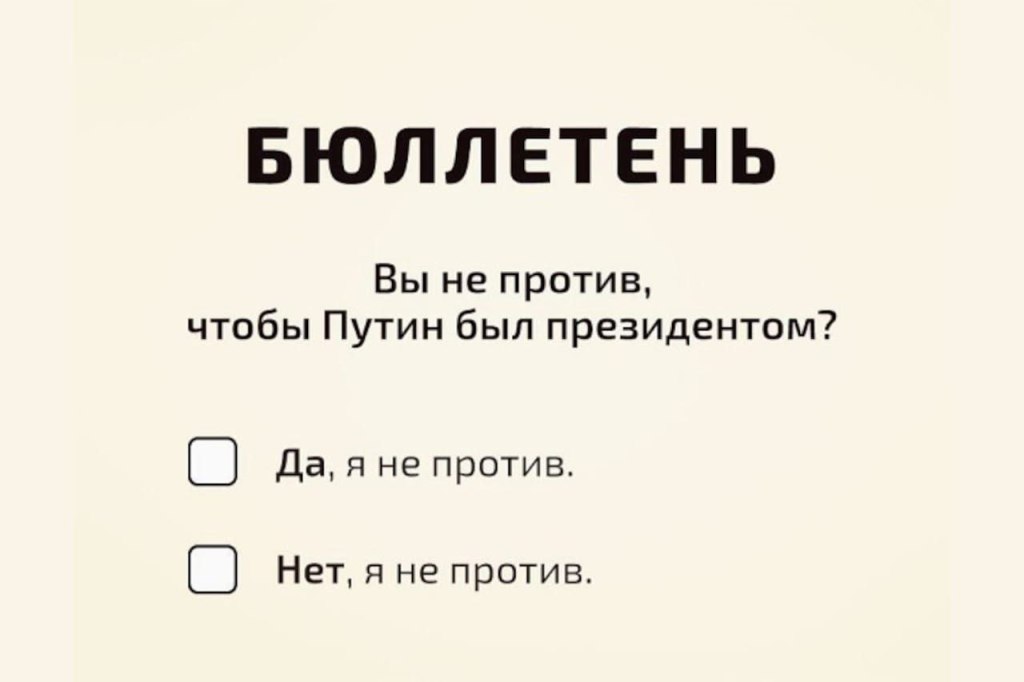

Ekaterina Schulmann in one of her August podcasts: ‘deprivatization and transfer of property in Russia is far more alarming to the elites than any loss of bits of Russian land, whether that land is canonical or non-canonical’. Schulmann in the same broadcast warned that direct measuring of public opinion is futile, but even the official pollsters can’t hide a real fall in the confidence of people in the centre.

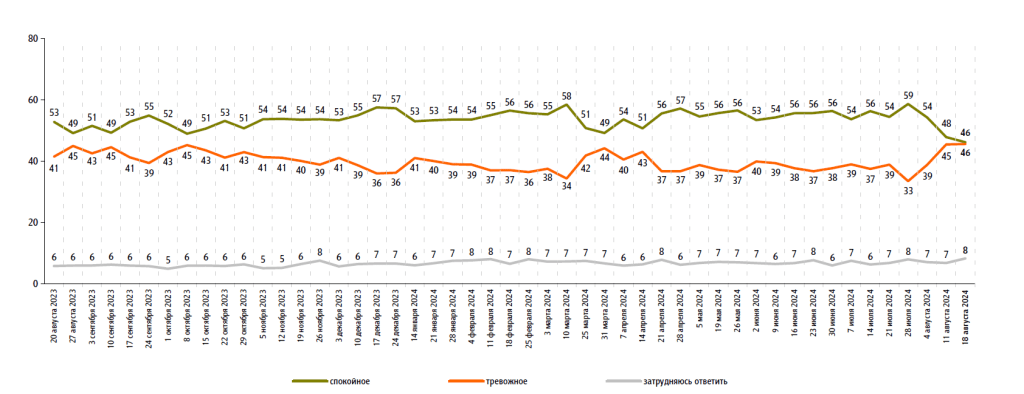

‘It is better to look at proxies’ for public opinion, is pretty much what everyone says now. There’s media consumption, internet search terms, politically ‘safer’ polls like the one about Russians’ biggest ‘fears’. But even here, Kursk does not register as much as one would expect. Schulmann gives a nice history of the relationship between ‘things are alarming/things are calm’ polling. In Feb. 2022 the split between alarming/calm was 55/39; Mobilization in late 2022: 70:26; Moscow drone strikes: 53/42. Now, post-Kursk: 46/46.

You can’t imitate Schulmann’s ironic style. She points out that when you ask Russians about the ‘Special Military Op’ they invariably speak like “schizos”: ‘Everything is going great… Let’s make peace right now!’ For Schulmann, we can compare Russian society to a person being smothered with a cushion while around them the world burns. In some sense they want to be smothered.

Viacheslav Inozemtsev, the Russian economic observer, covered the Kursk incursion in an interesting way. He notes that Kursk and Belgorod are centres of pork, poultry and milk production – 25% of pork production, in fact. Inozemtsev is more forthright than usual in the piece, arguing that new mobilization might be forced on the Kremlin by events like those in Kursk and that this would entail the defacto dismantling of Putinism. What he means by this is the ability of people to detach themselves from political life in the country, content that they will be largely left alone. If mobilization is needed, he seems to say, the system would have to fundamentally change, in order to survive.

Alexei Levinson, of Levada argues that Russians are indifferent to what’s happening in Kursk, citing, as usual, his brand of Wizard of Oz sociology: ‘focus group data showed that there was no significant concern’. He cites emotional anesthesia and numbness in the population, who seek denial and escape. This is a long interview and some readers will know I criticize Levada-type sociology on methodological grounds and more. Objection here, here, and here. But you don’t have to listen to me. Here are the words of Professor Gulnaz Sharafutdinova of KCL in her latest book on Rethinking Homo Sovieticus. Writing about the obsession of Levada with the totalitarian paradigm and the accusation of moral failure of the Russian people, ‘such a mixing of the political, the ethical and the analytical created “a blind spot” that many scholars did not see’ and that ‘labelling an entire society with the use of ideas from the 1950s is lamentable’. Why do observers like Levinson remain so wedded to the idea of inertia and atomization? (Rhetorical question. The answer is here)

That Levinson comes out with such a strong claim reveals more about the universe of ideas he lives in, than any empirical reality. I can’t help but mention a different ‘data point’ – vox pops that BBC’s Steve Rosenberg did in Aleksin after the Kursk incursion. Even though people knew they were talking to a foreign journalist with a camera, a very different, and charged atmosphere was evident (the subtitles are a bit misleading, by the way). And that chimes well with what I hear from people who are able to speak without restrictions to their friends, colleagues and relatives.

Holy war falls flat

One interlocutor noted that people struggle to connect with WWII tropes (resisting invasion as holy war) as a useable emotional catalyze, and that this has destabilizing effects, even as they are forced into using some of those same limiting tropes: heroism, sacrifice, faithfulness to the fatherland. Does this mean that through war, via ‘dialogic’ interaction of old tropes which are inadequate with the ‘new’ reality, a novel orientation towards the future might emerge? I can’t help think of a different kind of belatedness, this time relating to hegemonic cultural orders. In a society like Russia we must be doubly sensitive to the notion that organic crises (which we can argue Russia has been in for at least 15 years, or longer) eventually culminate with such unpredicted rapidity, that they overtake even the key actors involved. Indeed, this isn’t about the end of the Russian state or Putin – they may both ‘continue’ seemingly in their present form, even while overall the system transitions to a new steady-state and new forms of ‘common sense’ take over. Essentially the crisis might even resolve itself before we know it has, and be recognizable as such only much later. ‘Everything must change, so that everything remains the same’. Is this so different from Andrei Pertsev’s musings here on the cross-over in trends for relative popularity of Head of State and government

But back to those vox pops and my own interactions: when people use familiar tropes of heroism, these is a strange hybrid of sacredness and meaninglessness and also criticism of the army and civilian authorities.

If emotions performed publicly are political performances, then Kursk shows that the mechanism of performance itself is broken. This is even visible in the comments about it from people like Kara-Murza. Because rationality and emotion collide in his answer, his usually eloquent expression is literally blocked. He has to go off on a long tangent to get to the point of saying, rather tiredly, that he doesn’t like seeing Russians being killed just as he doesn’t like seeing Ukrainians murdered. ‘Strashno… strashno…. Strashno… bol’… strashno.’ [horror, horror, horror, pain, horror] overtake his whole commentary for a while. Until he comes out with the trite: ‘all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.’

In the end there can be neither rationality nor affectivity: things that the surveys like Levinson’s are aimed at measuring, as if they can be extracted as distilled fractions. Instead, there is a large (or small), depending on the person, black hole, about which there is nothing to say. Because the blockage of different orders of expression and feeling is right inside you. You can only shout into a void. But this too is not normalization of war, but like an explosion in the deep and dusty places where different available hegemonic discourses are stored.

For a while now the sociological person has ‘died’; it’s not that they are traumatized, which might be more true of Ukrainian victims. It means they are living in what Irina Sandomirskaya calls a ‘blockade economy’ a ‘powerful proving ground for the testing of technologies of power’. One in which money and power, and death and destruction overwhelm the capacity to gather together one’s own circulating and contradictory thoughts as meaningful currency.